How to Share a Secret (Diffie-Hellman-Merkle)

Diffie-Hellman-Merkle is a way to share a secret key with someone (or something) without actually sending them the key. Before we look into how we share keys let’s first look into what keys are and why we would want to invent a method to share keys without giving the other person the key.

Your front door is usually locked by a key. This key unlocks & locks your front door. You have one key which you use to unlock and lock things.

Only people with the key or a copy of the key can unlock the door. Now, imagine you’re going to be on holiday Friday, Saturday, Sunday in Bali. You want to invite your friend around to look after your cat 😺 while you’re on the beautiful beaches 🏖️.

Your only friend is unfortunately on holiday Wednesday, Thursday and Friday. They get back right as you leave for holiday. You can’t be there to physically give them the key, but hiding the key under a rock outside your door seems insecure. Anyone could lift up that rock and find the key, but you just want your friend to have the key.

This is where Diffie-Hellman comes in. Well, with Diffie-Hellman you’re not exchanging physical keys but rather digital keys. Let’s explore some basic cryptography to understand why digital key exchange sucks just as much as real life key exchange.

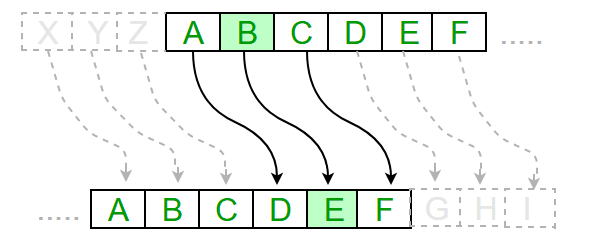

Julius Caesar used a cipher to send messages that no one else could read other than the intended recipient. Mainly because no one could read back in 100 BC, and those that could wouldn’t understand a random string of letters. That’s the whole point of cryptography. To create ways to communicate without third parties understanding the message. This cipher is Caesar*‘s Cipher*. Given an alphabet and a key (the key is an integer between 1 and 25), shift all of the alphabet letters by key.

With a shift of 3, as seen in the image above, A becomes D, B becomes E and so on until it wraps around with X = A. The original message is called the *plaintext *and the encrypted message is called the ciphertext.

The easiest way to perform Caesar’s Cipher is to turn all of the letters into numbers, a = 1, b = 2, c = 3 and so on.

To encrypt, E, you calculate this for every letter (where s is the shift):

$$ E_{s}(letter) = (letter + shift)$$

To decrypt Caesar’s cipher, D, you calculate this for every letter:

$$D_{s}(letter) = (letter - shift)$$

Something important to note is that this version of the cipher doesn’t support wraparound (for brevity).

As you can tell, it’s not very secure. With 25 total shifts you just have to shift the text 25 times until you find the decrypted code, this is called a brute force attack. You take the encrypted text and shift it all 25 times until you find the decrypted text. But let’s imagine for a second that this was a hard cipher - that brute force isn’t feasible.

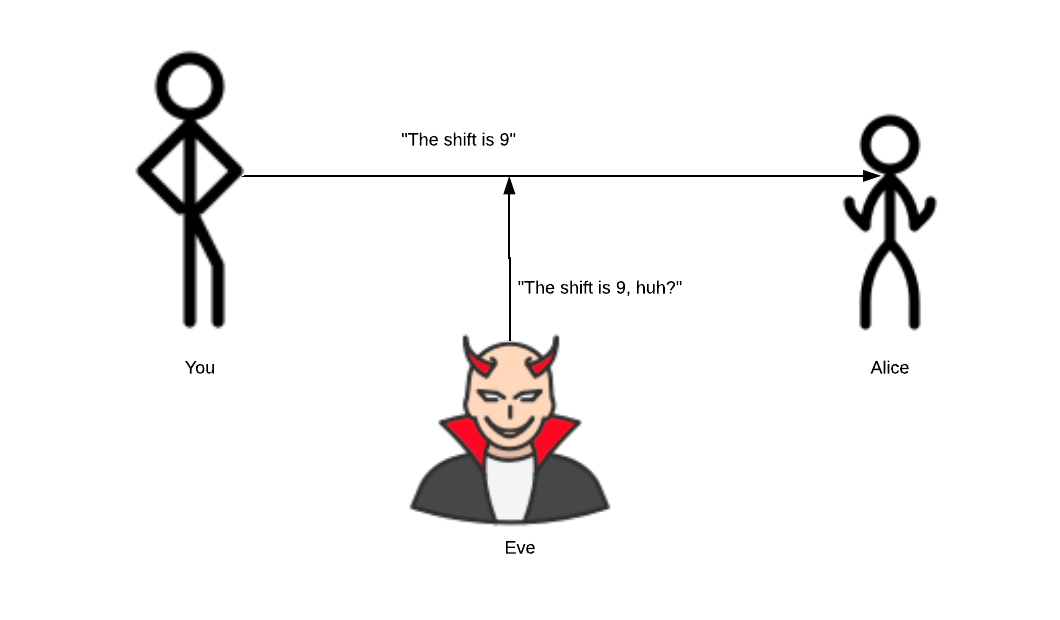

The shift is the key to Caesar’s cipher. But the problem still persists, how do you tell your friend you’re using a shift of 9? Any and all forms of communication can be listened in on. It doesn’t matter if you’re writing a letter or going to a hidden forest in Switzerland 30 miles from the nearest town. If you communicate the key, it can be listened in on.

How do you tell your friend you’re using a shift of 9, for example? You have to communicate it to them somehow. Any and all forms of communication can be listened in on - whether that’s writing a letter or going to a hidden forest in Switzerland 30 miles from the nearest town and telling your friend.

The problem becomes even more apparent when you realise that communicating parties over the internet usually have no prior knowledge about each other and are thousands of miles apart. This is where the magic of Diffie-Hellman-Merkle key exchange comes in.

Diffie-Hellman-Merkle

Diffie-Hellman is a way to securely exchange keys in public. It was conceptualised by Ralph Merkle, and named After Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman. I have chosen to include Merkle’s name as the title because he put in just as much work as Diffie-Hellman and his name never appears when this algorithm is talked about.

U.S. Patent 4,200,770, from 1977, is now expired and describes the now-public-domain algorithm. It credits Hellman, Diffie, and Merkle as inventors.

Let’s go through how this algorithm works.

- Pick two numbers, G and N.

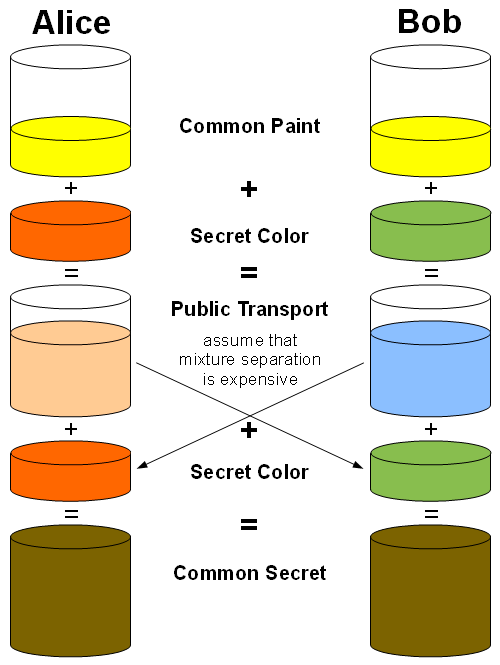

For this algorithm, we will also walk through the colour mixing method for explaining how it works.

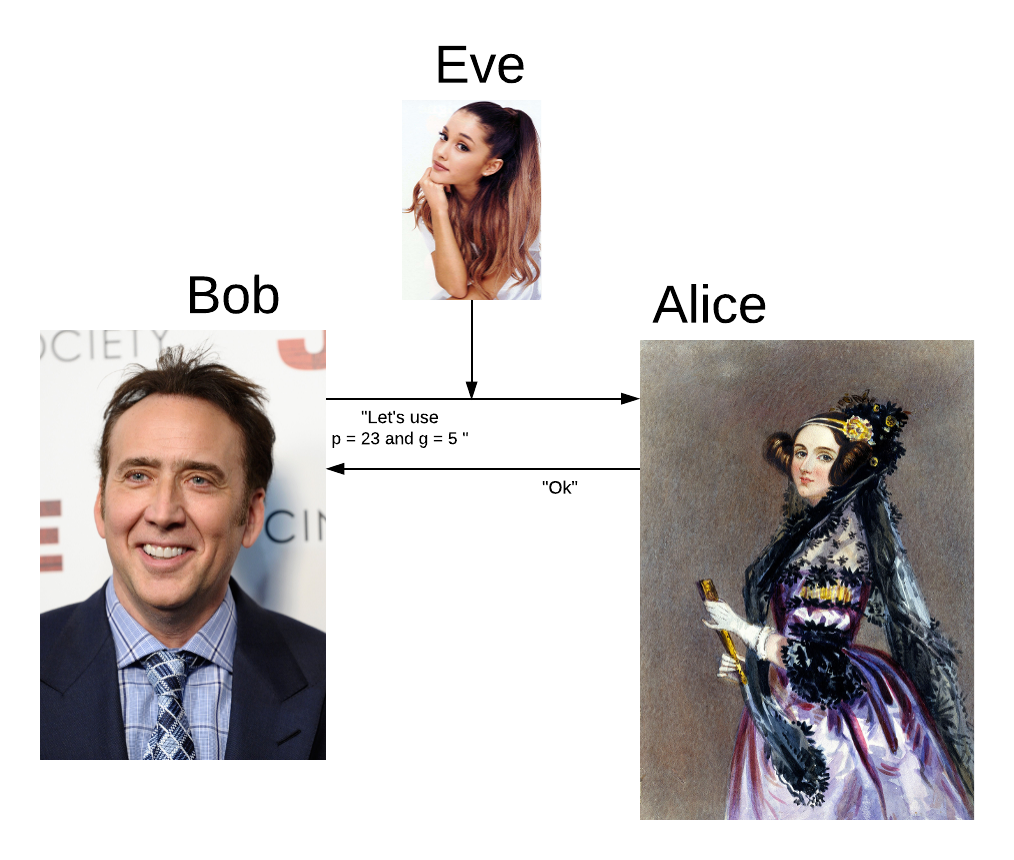

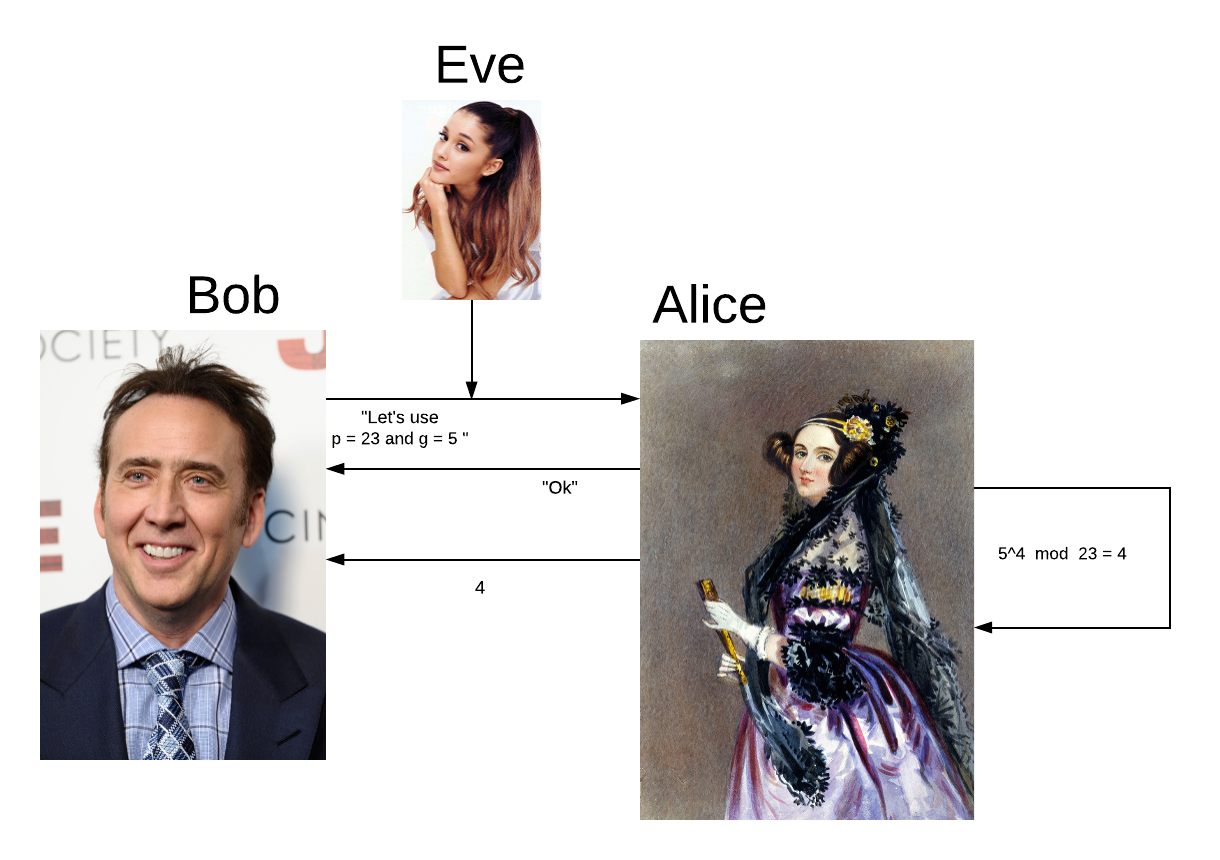

Alice and Bob publicly agree to use a modulus p = 23 and g = 5 (which is a primitive root modulo 23, explained later). Modulus is just the remainder of the division. Note: this example comes from Wikipedia.

It’s hard to describe the painting method in text, so if you want to know about this method I suggest watching this video:

We’ll colour G yellow. We have 2 copies of G (yellow) as seen above.

When Alice and Bob agree on these numbers, Eve knows they are using these numbers.

2. Alice needs to calculate a private key.

She does this by picking a secret number (a). She computes Ga mod p and sends that result to Bob.

Alice chooses a secret, random integer a = 4.

Alice computes A = 54 mod 23 = 4 and sends the number 4 to Bob.

She colours this private key reddish-brown.

Eve doesn’t know Alice’s secret number is 4, only that the result of this equation is 4. It’s not feasible for Eve to calculate what Alice’s secret number is from the resultant of this equation.

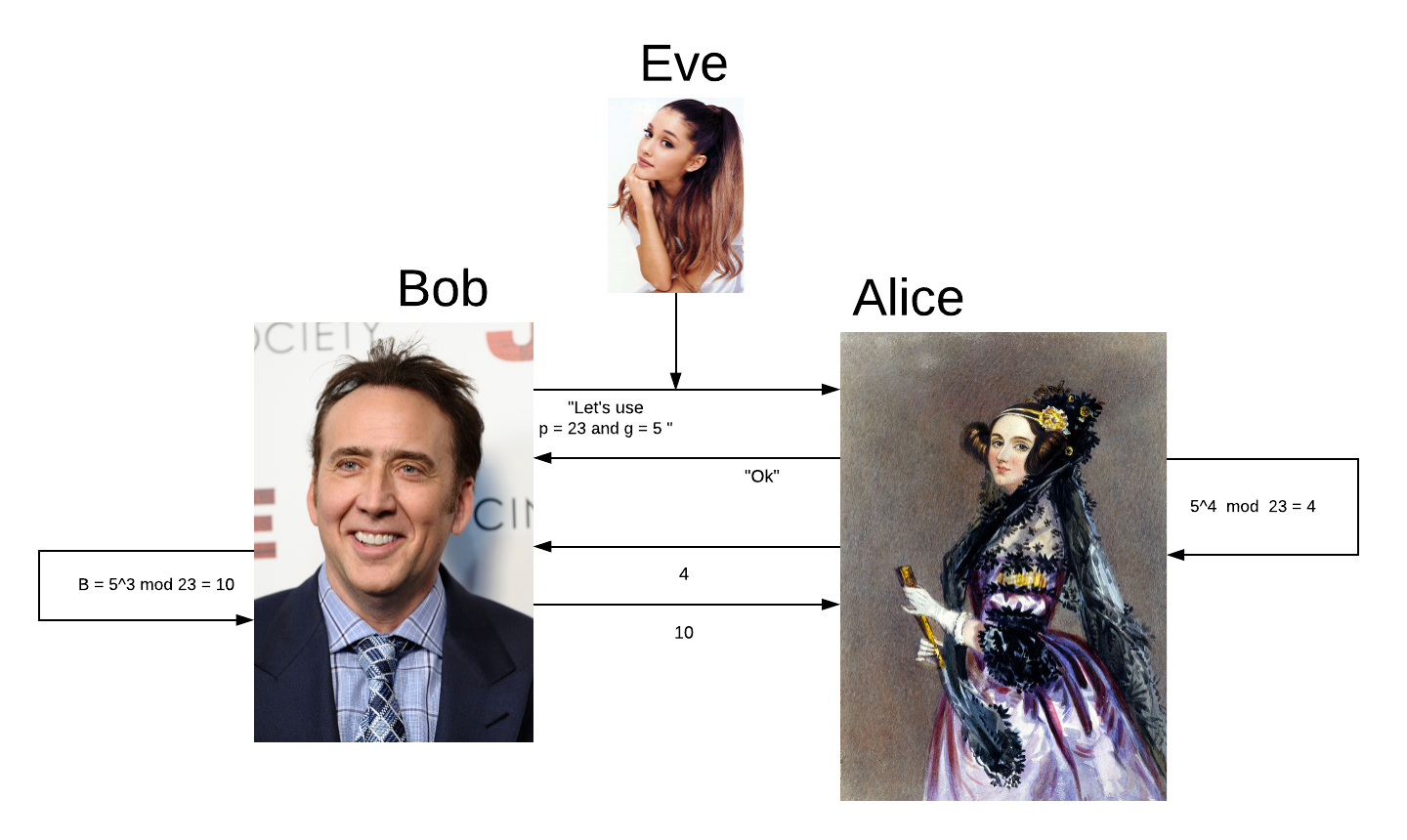

3. Bob makes his own private key. Its colour is dark green.

He calculates this by picking a secret number (b) and computes gb mod p. He then sends the result to Alice. Bob creates a random private key, for this example we’ll use 3.

Then Bob calculates b = 53 mod 23 = 10 and sends 10 to Alice.

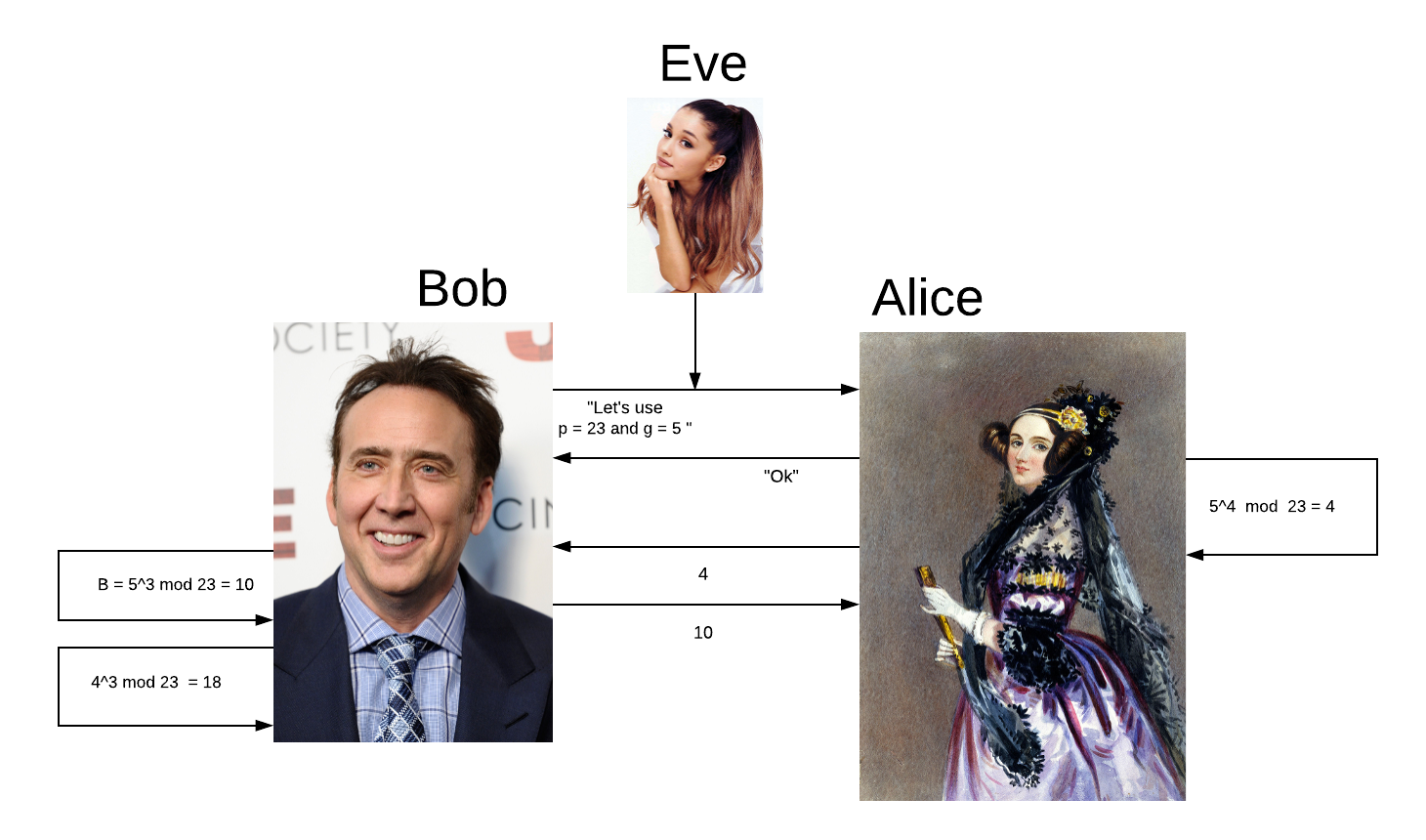

4. Now Bob takes the number Alice sent him and computes ba mod p.

In the colour analogy, this is taking Alice’s paint colour and adding it to Bob’s paint colour.

Bob computes s = 43 mod 23 = 18.

Bob doesn’t send this to Alice.

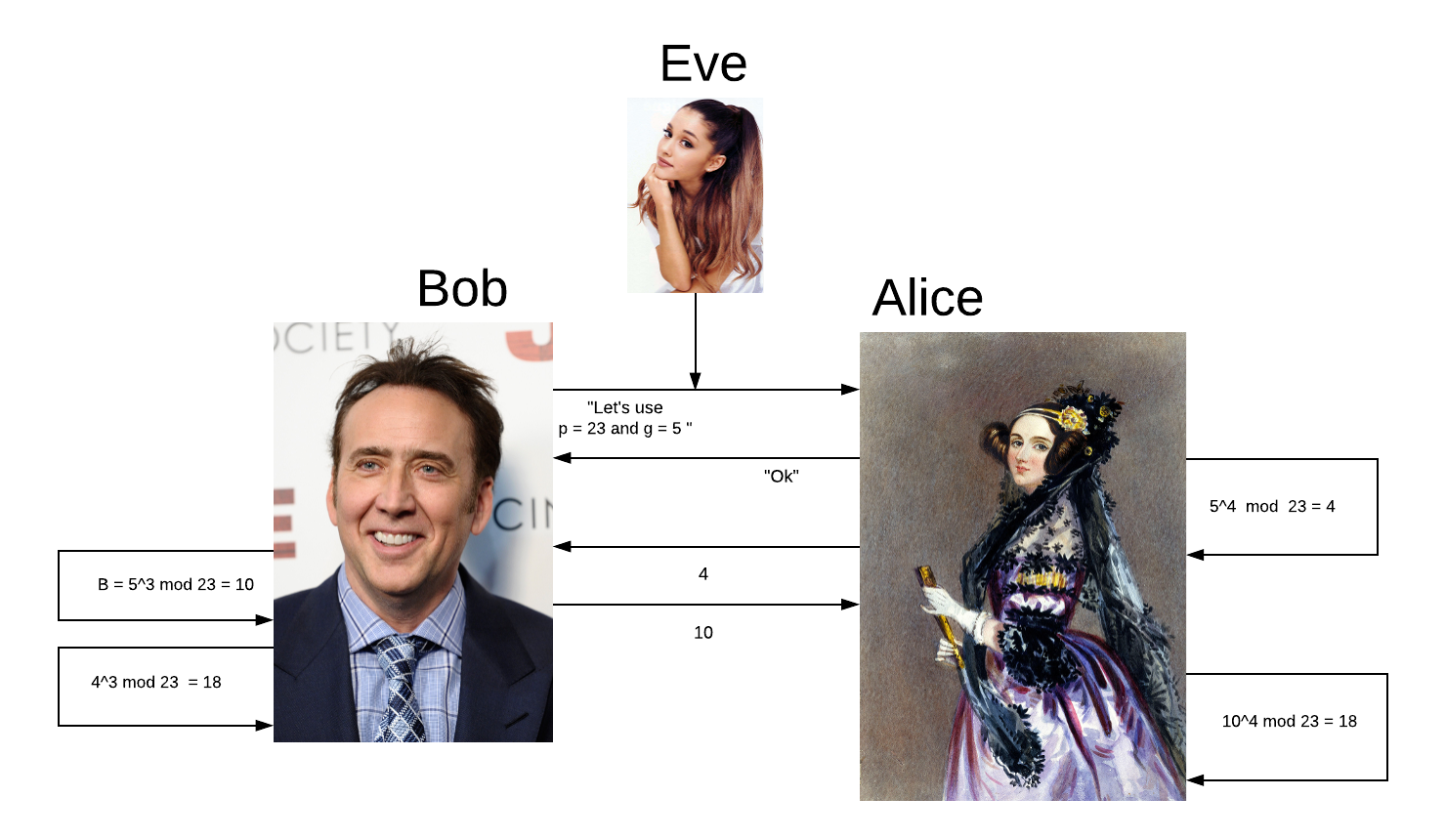

5. Alice computes ab mod p.

In the paint analogy, this is Alice adding Bob’s paint (that Bob sent her) to her painting.

Alice calculates s = 104 mod 23 = 18

The magic is that Alice and Bob now have the same number or the same paint colour.

Let’s discuss in detail the mathematics behind this cool algorithm.

Explanation of maths

Diffie-Hellman-Merkle works because of a cool modulus exponent principle. First, let’s explain what modulus is before we try to understand this principle.

Modular Arithmetic

Imagine a finite range of numbers, for example, 1 to 12. These numbers are arranged in a circle, much like a clock (modular arithmetic is sometimes called clock arithmetic because of this).

Count 13 around this clock. You get to 12 and then you need to count 1 more - so you go back to 1. Modular arithmetic is still defined as the remainder of division, however, it can also be defined (and is more commonly defined) as a clock.

Functions using modular arithmetic tend to perform erratically, which in turn sometimes makes them one-way functions. Let’s see this with an example by taking a regular function and seeing how it works when it becomes a modular arithmetic function.

$$3^x$$

When we insert 2 into this function, we get 32 = 6. Insert 3 and we get 33 = 9.

This function is easy to reverse. If we’re given 9, we can tell that the function had an input of 3, because 33 = 9.

However, with modular arithmetic added, it doesn’t behave sensibly.

Imagine we had this formula:

$$3^{x} mod 7$$

How would you find out what x is? You can’t put the mod on the other side, because there isn’t really an inverse of modular arithmetic. What about guessing? Let’s input 5:

$$3^{5} mod 7$$

Okay, that was too big. You might want to go lower, maybe 4 or 3 but actually this is the wrong direction. When x is 6, it is equal to 1.

In normal arithmetic, we can test numbers and get a feel for whether we are getting warmer or colder, but this isn’t the case with modular arithmetic.

Often the easiest way to reverse modular arithmetic is to compile a table for all values of x until the right answer is found. Although this may work for smaller numbers, it is computationally infeasible to do for much larger numbers. This is often why modular arithmetic is known as a one-way function.

If I gave you a number such as 5787 and told you to find the function for it, it would be infeasible. In fact, if I gave you the ability to input any number into the function it would still be hard. It took me a mere few seconds to make this function, but it’ll take you hours or maybe even days to work out what x is.

Diffie-Hellman-Merkle is a one-way function. While it is relatively easy to carry out this function, it is computationally infeasible to do the reverse of the function and find out what the keys are. Although, it is possible to reverse an RSA encryption if you know some numbers such as N.

Primitive root

The primitive root of a prime number, p, is a number, a, such that all numbers:

$$a \; mod \; p, a^2 mod p, a^3 \; mod \; p, a^4 \; mod \; p, ...$$

are different. There is a formula for counting what the indices are, but I think it’s far more intuitive to acknowledge “the second one is to the power of 2, the third one is to the power of 3” and so on.

Let's see an example where $p = 7$. Let's set $a_1 = 2$ and $a_2 = 3$.

$$2^0 = 1 ( mod \ 7) = 1$$

$$2^1 = 2 ( mod \ 7) = 2$$

$$2^2 = 4 ( mod \ 7) = 4$$

$$2^3 = 8 ( mod \ 7) = 1$$

Uh oh! 20 is the same as 23. This means that 2 is not a primitive root of 7. Let’s try again with 3.

$$3^0 = 1 ( mod \ 7) = 1$$

$$3^1 = 3 (mod \ 7) = 3$$

$$3^2 = 9 (mod \ 7) = 2$$

$$3^3 = 27 (mod \ 7) = 6$$

$$3^4 = 81 ( mod \ 7) = 4$$

$$3^5 = 243 ( mod \ 7) = 5$$

$$3^6 = 1 (mod \ 7) = 1$$

Now let’s try a = 3.

$$3^0 = 1$$

$$3^1 = 3$$

$$3^2 = 2$$

$$3^3 = 6$$

$$3^4 = 4$$

$$3^5 = 5$$

$$3^6 = 1$$

Now we’ve got a cycle in these powers.

36 = 1, and 30 = 1. This is because we are using modulus it repeats into this cycle, so we can stop now. Unlike before where we reached 23 and it cycled, it's okay if it cycles here because for any prime number, p, and any number, a, such that \(a \ne 0 \ mod \ p\) and \(a \ne 1 \; mod \; p\) the consecutive powers of \(a\) may cover no more than p - 1 values modulo p. That is, we go from \(1, ..., p - 1\). When p is 7, the consecutive powers cover up to 6.

Discrete logarithms

$$a^b = c \; mod \; n$$

Such an equation means some numbers you can write it differently as:

$$log_a c = b \; mod \; n$$

Logarithms are the inverse of exponents, we’ve just inversed the sum here.

Now it’s a well-defined function, we can say in discrete terms that \(log_3 5 = 5 \ (mod \ 7)\) (looking at the table above).

if you use a non-primitive root number it becomes easier, as we have a smaller number of outcomes (because it repeats earlier), as seen below.

$$2^0 = 1 (mod \ 7) = 1$$

$$2^1 = 2 ( mod \ 7) = 2$$

$$2^2 = 4 ( mod \ 7) = 4$$

$$2^3 = 8 ( mod \ 7) = 1$$

By using a primitive root, we get a much larger outcome, making it harder.

$$3^0 = 1 ( mod \ 7) = 1$$

$$3^1 = 3 (mod \ 7) = 3$$

$$3^2 = 9 ( mod \ 7) = 2$$

$$3^3 = 27 ( mod \ 7) = 6$$

$$3^4 = 81 ( mod \ 7) = 4$$

$$3^5 = 243 ( mod \ 7) = 5$$

$$3^7 = 1 ( mod \ 7) = 1$$

It is relatively easy to calculate exponentials modulo a prime, that is a, l, p calculate ai mod p.

Exponentiation is a cheap operation. you can do it even for very large numbers while logarithm is a much more difficult function to calculate for large numbers.

To calculate exponentiation, you give number 2 and you respond to me what the answer is. that’s exponentiation, going from left to right.

$$3^0 = 1$$

$$3^1 = 3$$

$$3^2 = 2$$

$$3^3 = 6$$

$$3^4 = 4$$

$$3^5 = 5$$

Logarithm is how to go back, from right to left. Logarithms are much harder than exponentiation.

Maths implemented

Let’s go back to seeing how Diffie-Hellman worked, but this time with a lot more knowledge of how mathematics works.

We have 2 people, Alice and Bob. Each of them has to agree in advance on some prime number q (publicly known number) and its primitive root a (publicly known).

1. Alice selects a random integer \(x_a < q\) and keeps it in secret

2. B selects a random integer \(x_b < q\) and keeps it in secret

3. Alice calculates the function left to right (exponentiation)

$$3^0 = 2$$

$$3^1 = 3$$

$$3^2 = 2$$

$$3^3 = 6$$

$$3^4 = 4$$

$$3^5 = 5$$

and they choose one of the exponents, chosen randomly and kept in secret. Now Alice does \(y_a = a^{x a} mod q\) and sends it to Bob.

This example isn’t very impressive, and sometimes 35 = 5 but for much larger numbers most things change everything, this is almost RSA encryption (the idea is the same, but it’s not quite the same as this is key exchange, not encryption).

Bob then does the same as Alice. Both Alice and Bob are now capable of calculating the shared key.

Alice calculates \(k = (y_b)^{x_a} \; mod \; q\)

Bob calculates \(k = (y_a)^{x_b} \; mod \; q\)

Now they have the same numbers, k is the common secret key.

$$(\alpha ^ {x_b})^{x_a} = (\alpha ^ {x_a})^{x_b}$$

This equation above is what makes it all work. The formulae are the same, but different. You get Alice to do one side of the formula, Bob does another side and they end up with the same number.

This really is the equation that puts it all together. Most of this blog post led up to this equation.

a and b are secret, and without these numbers, there is no easy way to repeat these computations because in to do it you need to know the secrets.

The above formula shows that the two methods are exactly equal. If you do the left equation, you get the same result as the right equation.

Conclusion

Diffie-Hellman-Merkle is a fascinating way of sharing a secret over an unsecured communications medium, by not sharing it at all over that medium.