How Does Tor Really Work? The Definitive Visual Guide (2023)

Today, we’re going to do a technical deep-dive into how Tor really works.

No mention of how to access Tor, no mention of what might be on Tor. This is how Tor works.

Without speculation and without exaggeration of what Tor is. Just a deep dive into the technical stuff of how Tor works.

This article is designed to be read by anyone, with **ZERO **knowledge on networking or Tor.

Let’s dive right in.

🗻 What is Tor?

The United States Naval Research Laboratory developed The Onion Routing Protocol (Tor) to protect U.S. intelligence communications online. Ironically, Tor has seen widespread use by everyone - even those organisations which the U.S. Navy fights against.

You may know Tor as the hometown of online illegal activities, a place where you can buy any drug you want, and a place for all things illegal. Tor is much larger than what the media makes it out to be. According to Kings College much of Tor is legal.

When you normally visit a website, your computer makes a direct TCP connection with the website’s server. Anyone monitoring your internet could read the TCP packet. They can find out what website you’re visiting and your IP address. As well as what port you’re connecting to.

If you’re using HTTPS, no one will know what the message said. But, sometimes all an adversary needs to know is who you’re connecting to.

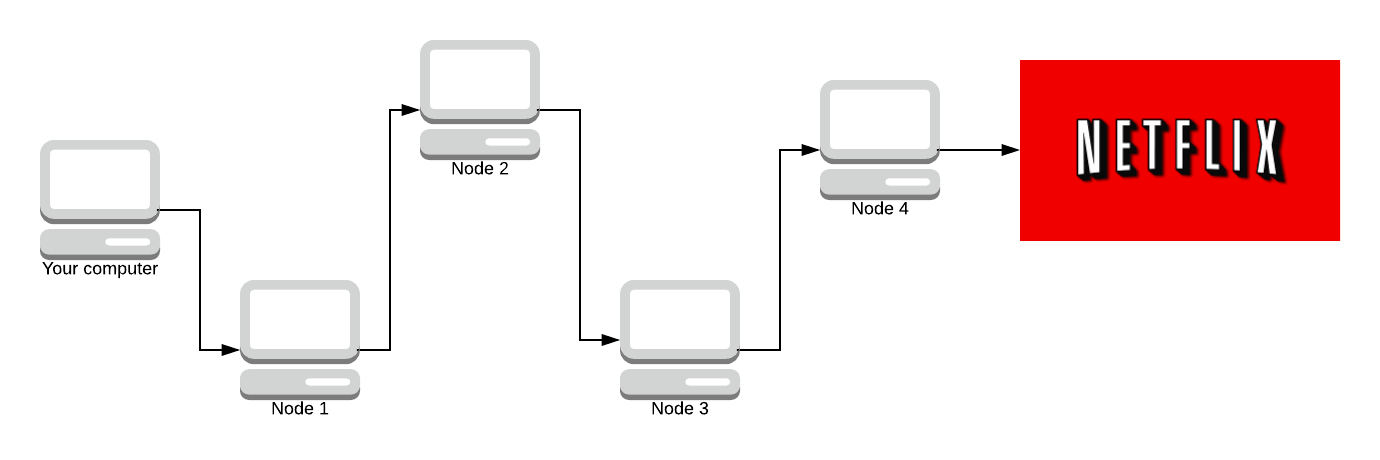

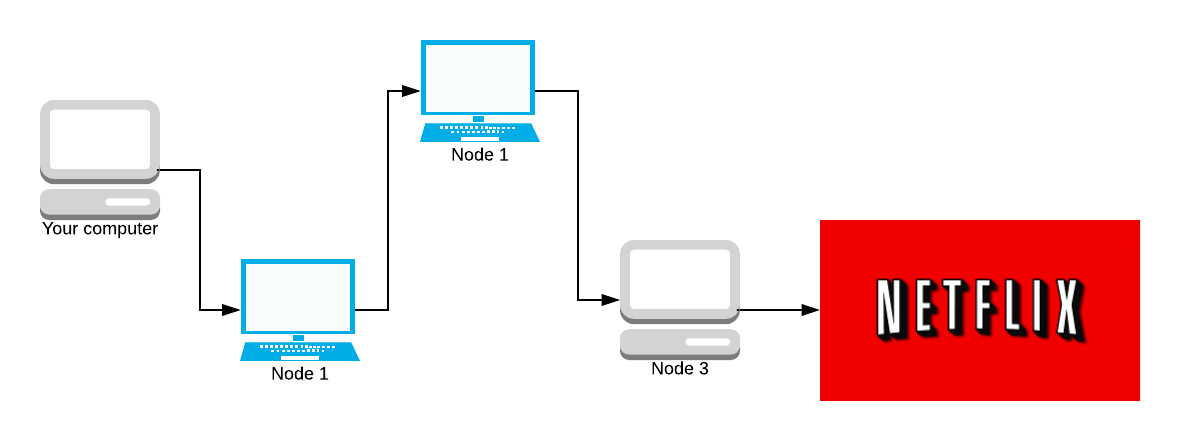

Using Tor, your computer never communicates with the server directly. Tor creates a twisted path through 3 Tor nodes and sends the data via that circuit.

The core principle of Tor is onion routing which is a technique for anonymous & secure communication over a public network. In onion routing messages are encapsulated in several layers of encryption.

“Onions have layers” - Shrek

So does a message going through Tor. Each layer in Tor is encryption, you are adding layers of encryption to a Tor message, as opposed to just adding 1 layer of encryption.

This is why it’s called The Onion Routing Protocol because it adds layers at each stage.

The resulting onion (fully encapsulated message) is then transmitted through a series of computers in a network (called onion routers) with each computer peeling away a layer of the ‘onion’. This series of computers is called a path. Each layer contains the next destination - the next router the packet has to go to. When the final layer is decrypted you get the plaintext (non-encrypted message).

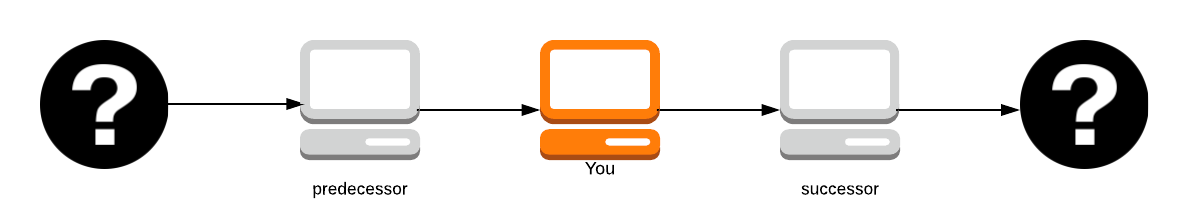

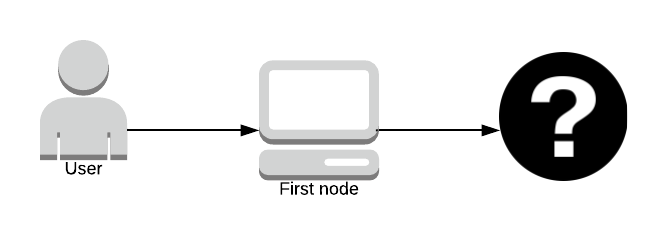

The original author remains anonymous because each node in the network is only aware of the preceding and following nodes in the path (except the first node that does know who the sender is, but doesn’t know the final destination).

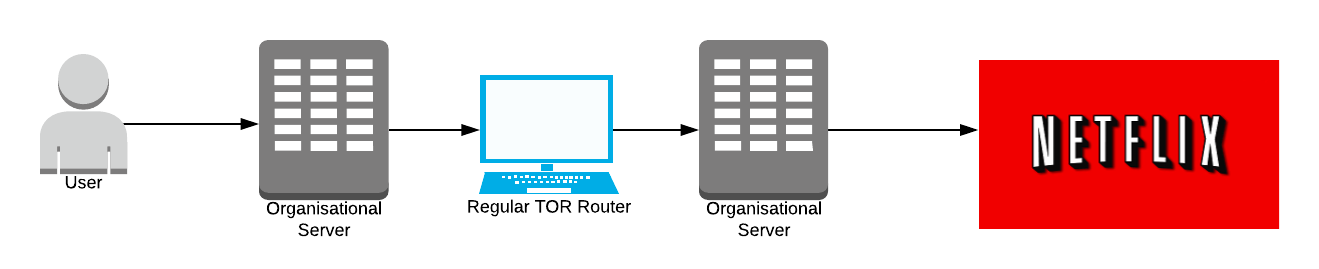

This has led to attacks where large organisations with expansive resources run servers to attempt to be the first and last nodes in the network. If the organisation’s server is the first node, it knows who sent the message. If the organisation server is the last node, it knows the final destination and what the message says.

Now we have a basic overview of Tor, let’s start exploring how each part of Tor works. Don’t worry if you’re confused, every part of Tor will be explained using gnarly diagrams 😁✨

🌎 Overview

Onion Routing is a distributed overlay network designed to anonymise TCP-based applications like web browsing, secure shell and instant messaging.

Clients choose a path through the network and build a circuit where each onion router in the path knows the predecessor and the successor, but no other nodes in the circuit. Paths and circuits are synonyms.

The original author (the question mark on the far left) remains anonymous unless you’re the first path in the node as you know who sent you the packet.

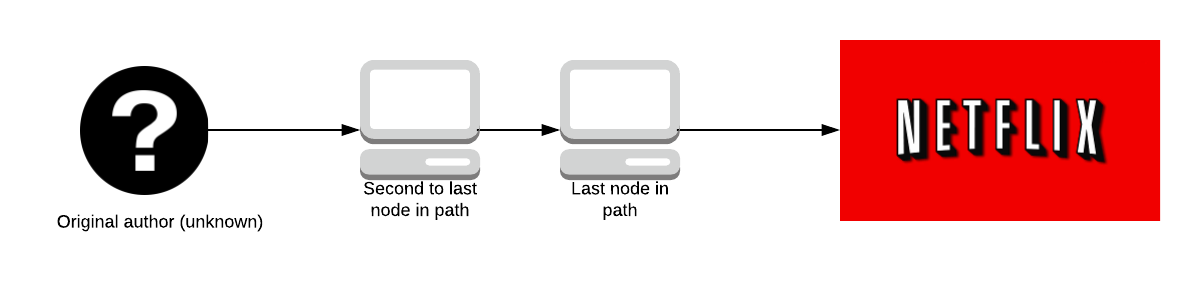

No one knows what data is being sent until it reaches the last node in the path; who knows the data but doesn’t know who sent it. The second to last node in the path doesn’t know what the data is, only the last node in the path does.

This has led to attacks whereby large organisations with expansive resources create Tor servers which aim to be the first and last onion routers in a path. If the organisation can do this, they get to know who sent the data and what data was sent, effectively breaking Tor.

Oh no! Now large organisation knows you watch Netflix 🍿

It’s incredibly hard to do this without being physically close to the location of the organisation's servers, we’ll explore this more later.

Throughout this article, I’ll be using Netflix as a normal service (Bob) and Amazon Prime Video as the adversary (Eve). In the real world, this is incredibly unlikely to be the case. I’m not here to speculate on what organisations might want to attack Tor, so I’ve used 2 unlikely examples to avoid the political side of it.

Each packet flows down the network in fixed-size cells. These cells have to be the same size so none of the data going through the Tor network looks suspiciously big.

These cells are unwrapped by a symmetric key at each router and then the cell is relayed further down the path. Let’s go into Tor itself.

👉 Tor Itself

There is strength in numbers

Tor needs a lot of users to create anonymity, if Tor was hard to use new users wouldn’t adopt it so quickly. Because new users won’t adopt it, Tor becomes less anonymous. By this reasoning, it is easy to see that usability isn’t just a design choice of Tor but a security requirement to make Tor more secure.

If Tor isn’t usable or designed nicely, it won’t be used by many people. If it’s not used by many people, it’s less anonymous.

Tor has had to make some design choices that may not improve security but improve usability with the hopes that an improvement in usability is an improvement in security.

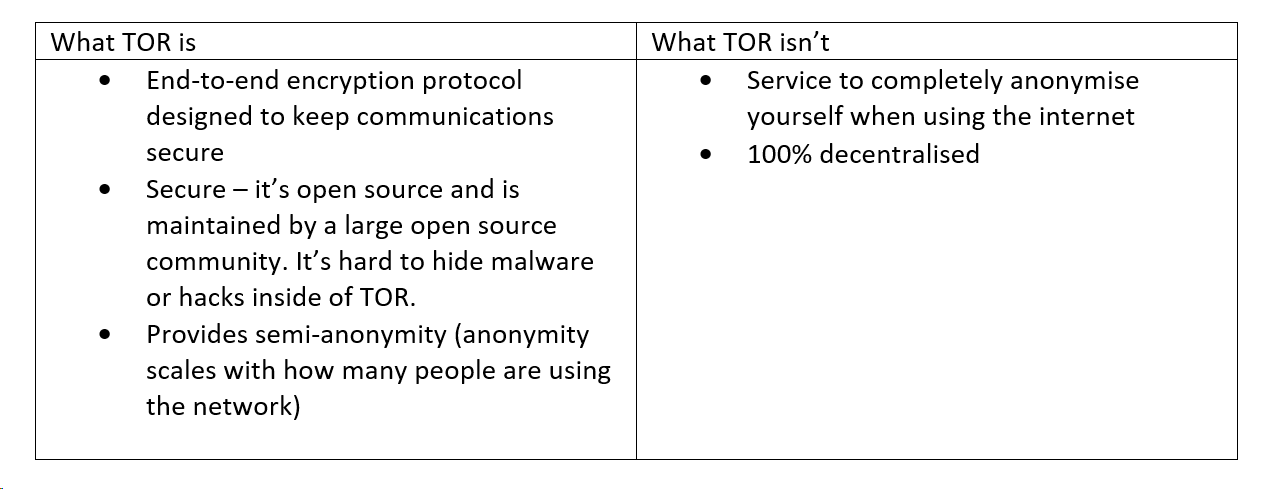

❌ What Tor Isn’t

Tor is not a completely decentralised peer-to-peer system like many people believe it to be. If it was completely peer-to-peer it wouldn’t be very usable. Tor requires a set of directory servers that manage and keep the state of the network at any given time.

Tor is not secure against end-to-end attacks. An end-to-end attack is where an entity has control of both the first and last node in a path, as talked about earlier. This is a problem that cyber security experts have yet to solve, so Tor does not have a solution to this problem.

Tor does not hide the identity of the sender.

In 2013 during the Final Exams period at Harvard, a student tried to delay the exam by sending in a fake bomb threat. The student used Tor and Guerrilla Mail (a service which allows people to make disposable email addresses) to send the bomb threat to school officials.

The student was caught, even though he took precautions to make sure he wasn’t caught.

Gurillar mail sends an originating IP address header along with the email that’s sent so the receiver knows where the original email came from. With Tor, the student expected the IP address to be scrambled but the authorities knew it came from a Tor exit node (Tor keeps a list of all nodes in the directory service) so the authorities simply looked for people who were accessing Tor (within the university) at the time the email was sent.

Tor isn’t an anonymising service, but it is a service that can encrypt all traffic from A to B (so long as an end-end attack isn’t performed). Tor is also incredibly slow, so using it for Netflix isn’t a good use case.

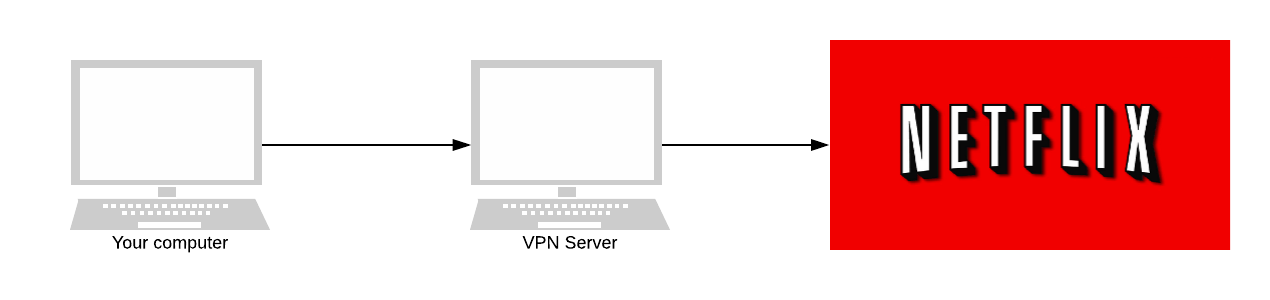

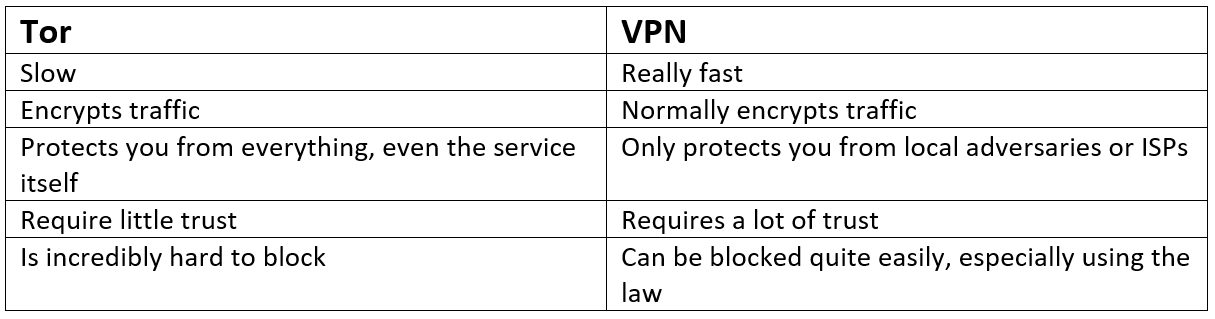

💻 The Difference Between Tor and a VPN

When you use a VPN, the VPN forwards all your internet traffic to the appropriate destination. When it does so, the VPN encrypts your traffic. All your internet service provider can see is encrypted traffic heading from your computer to the VPN.

They can’t see inside your packets. They don’t know who you’re talking to - other than the VPN.

VPNs aren’t private in the same way that Tor is. VPNs protect you against ISPs or local adversaries (ones monitoring your laptop’s WiFi). But, they don’t protect you from themselves.

The VPN is the man in the middle. It knows who you are and who you’re talking to. Depending on the traffic, the VPN also decrypts your packet. Meaning they know everything. With a VPN, you have to trust it. With Tor, you don’t have to put a lot of trust in it.

In Tor, one rogue node is survivable. If one of the nodes in our graph earlier was an adversary, they’ll only know our IP address or our data packet. Tor protects you from Tor. VPNs expect that you trust them.

Tor protects you from the Tor network. One rogue node is survivable. They don’t expect you to trust the network.

No one, apart from you, should know the IP addresses of the origin and destination - and know the contents of the message.

Now that we have a good handle on what Tor is, let’s explore onion routing.

🔐 Onion Routing

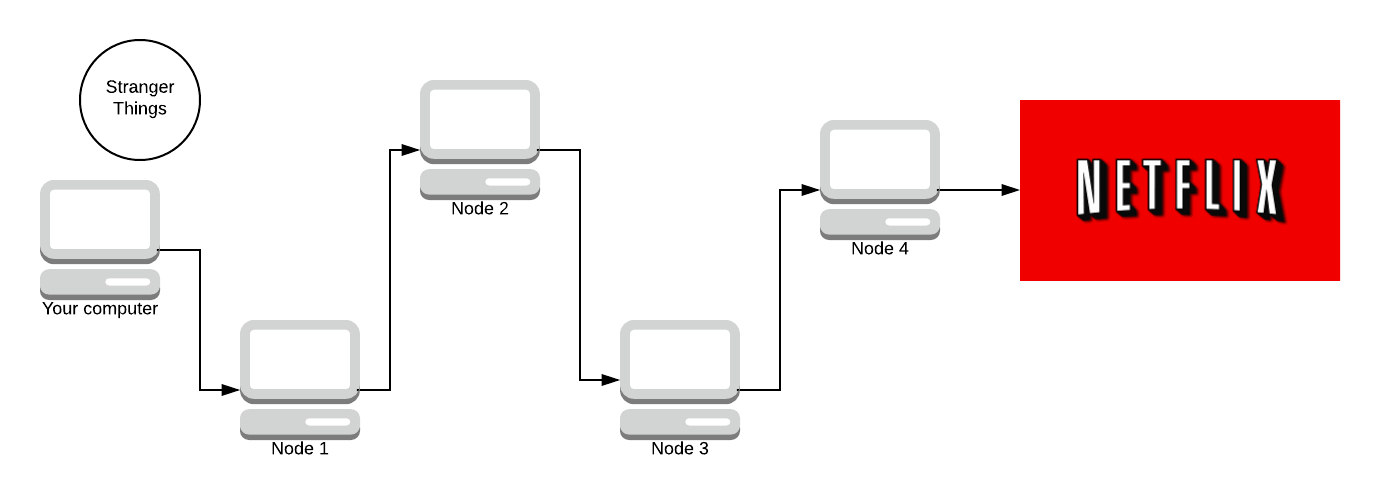

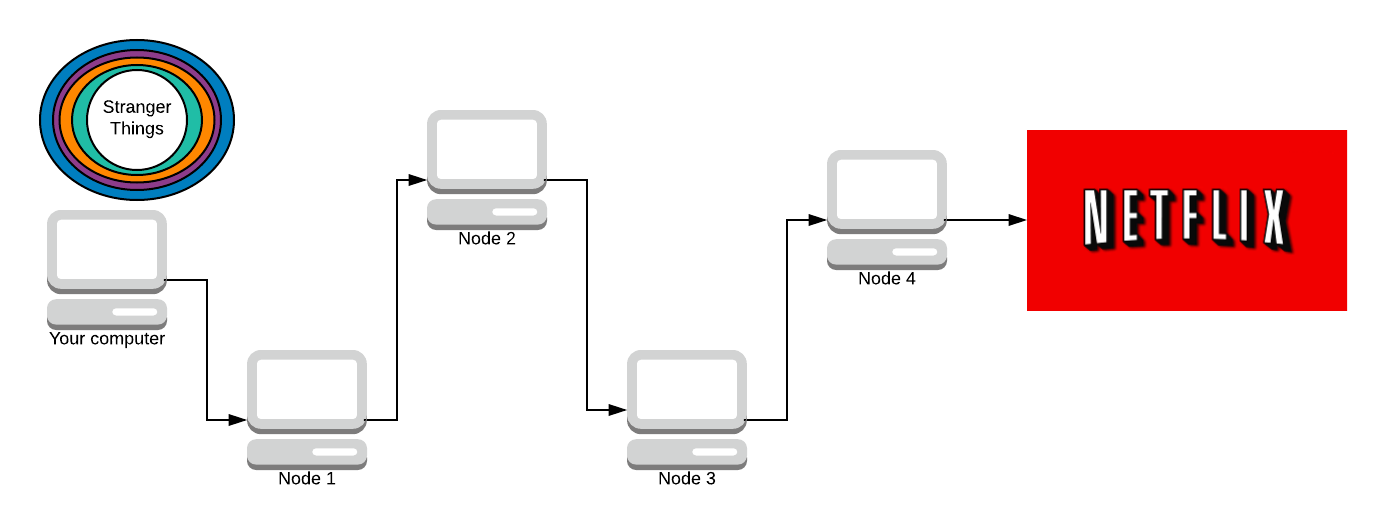

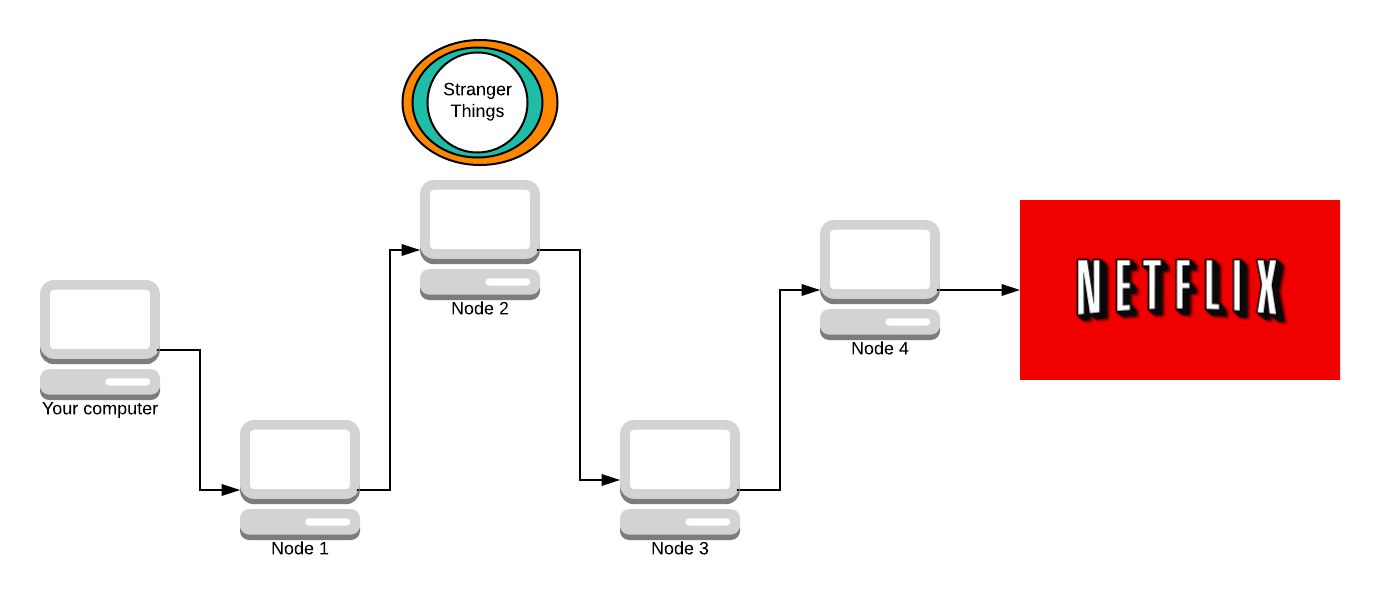

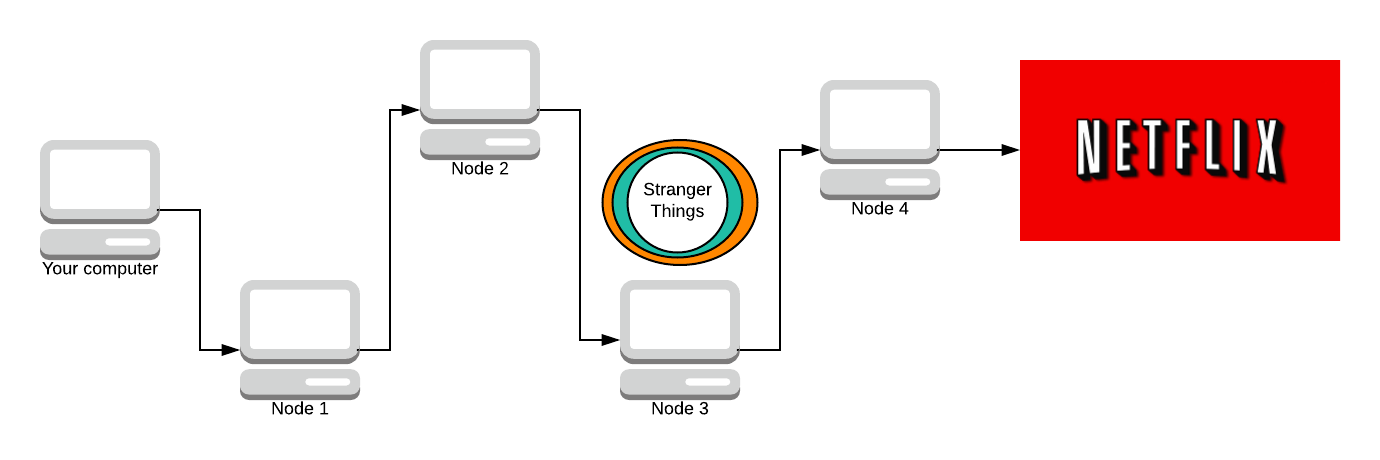

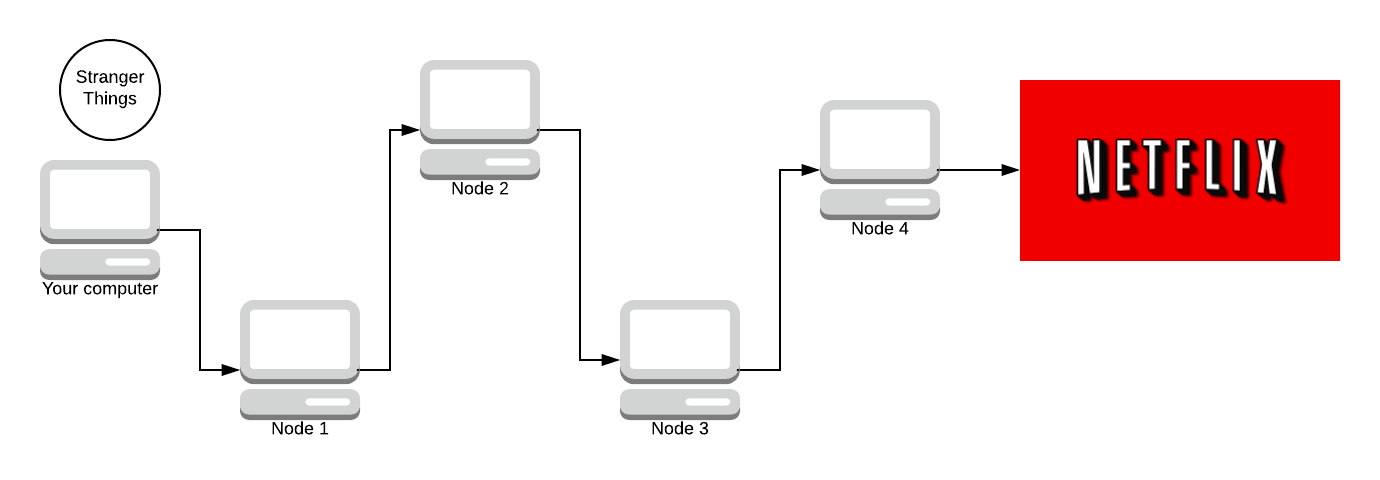

Given the network above, we are going to simulate what Tor does. Your computer is the one on the far left, and you’re sending a request to watch Stranger Things on Netflix (because what else is Tor used for 😉). This path of nodes is called a circuit. Later on, we’re going to look into how circuits are made and how the encryption works. But for now, we’re trying to generalise how Tor works.

We start off with the message (we haven’t sent it yet). We need to encrypt the message N times (where N is how many nodes are in the path). We encrypt it using AES, a symmetric key crypto-system. The key is agreed upon using Diffie-Hellman. Don’t worry, we’ll discuss all of this later. There are 4 nodes in the path (minus your computer and Netflix) so we encrypt the message 4 times.

Our packet (onion) has 4 layers. Blue, purple, orange, and teal. Each colour represents one layer of encryption.

We send the onion to the first node in our path. That node then removes the first layer of encryption.

Each node in the path knows what the key to decrypt their layer is (via Diffie-Hellman). Node 1 removes the blue layer with their symmetric key (that you both agreed on).

Node 1 knows you sent the message, but the message is still encrypted by 3 layers of encryption, it has no idea what the message is.

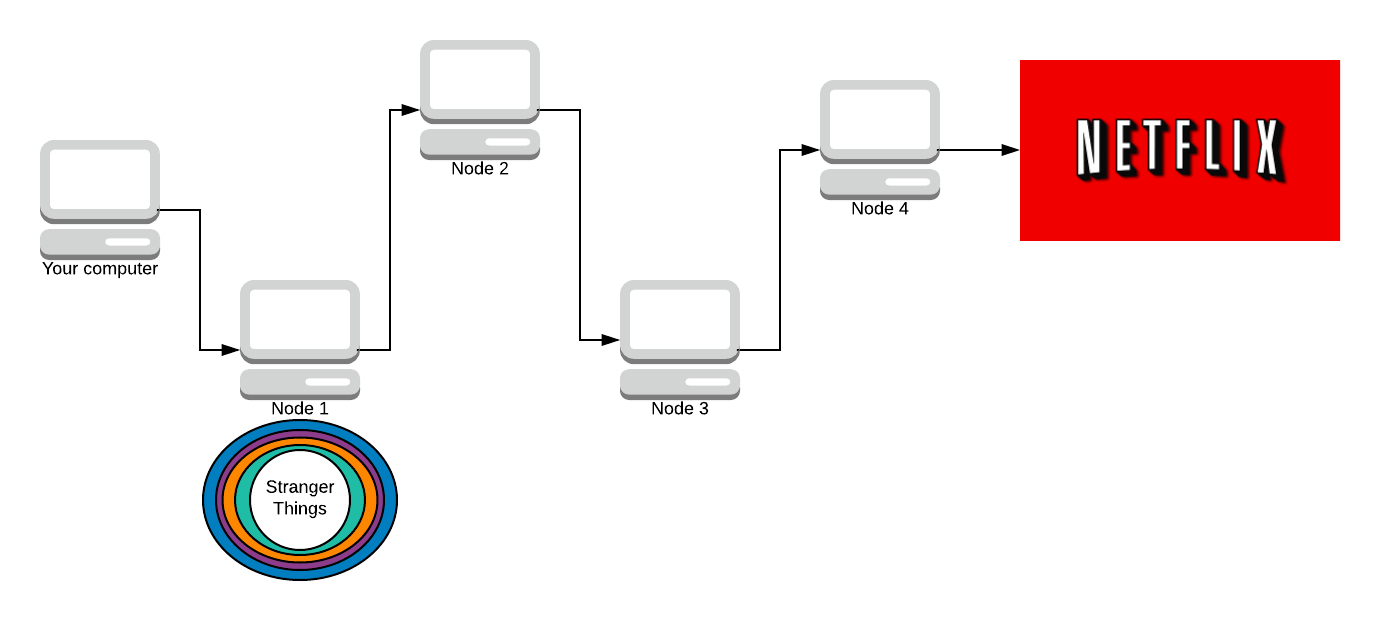

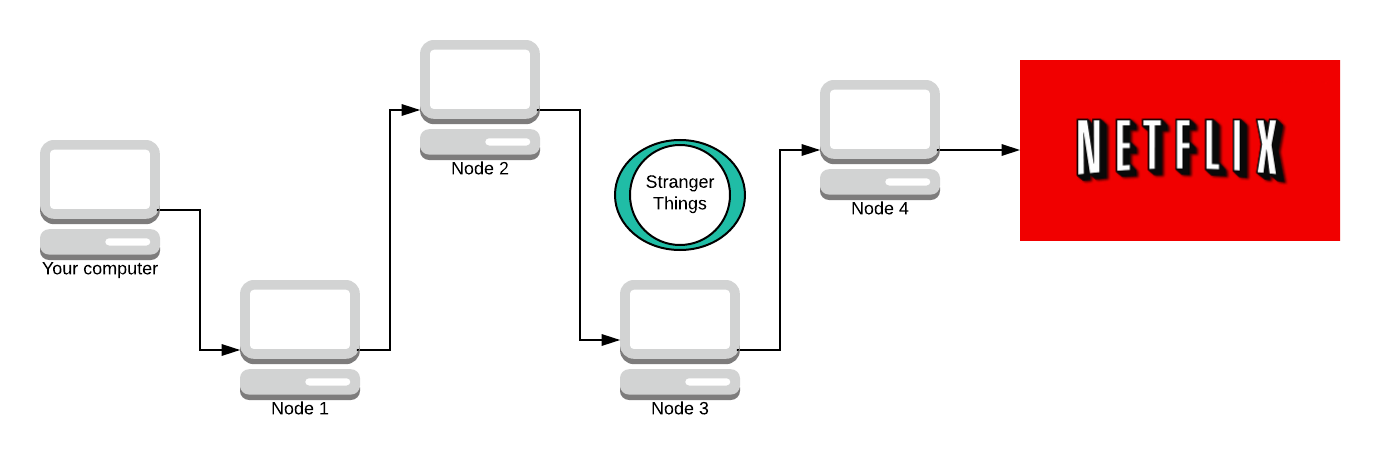

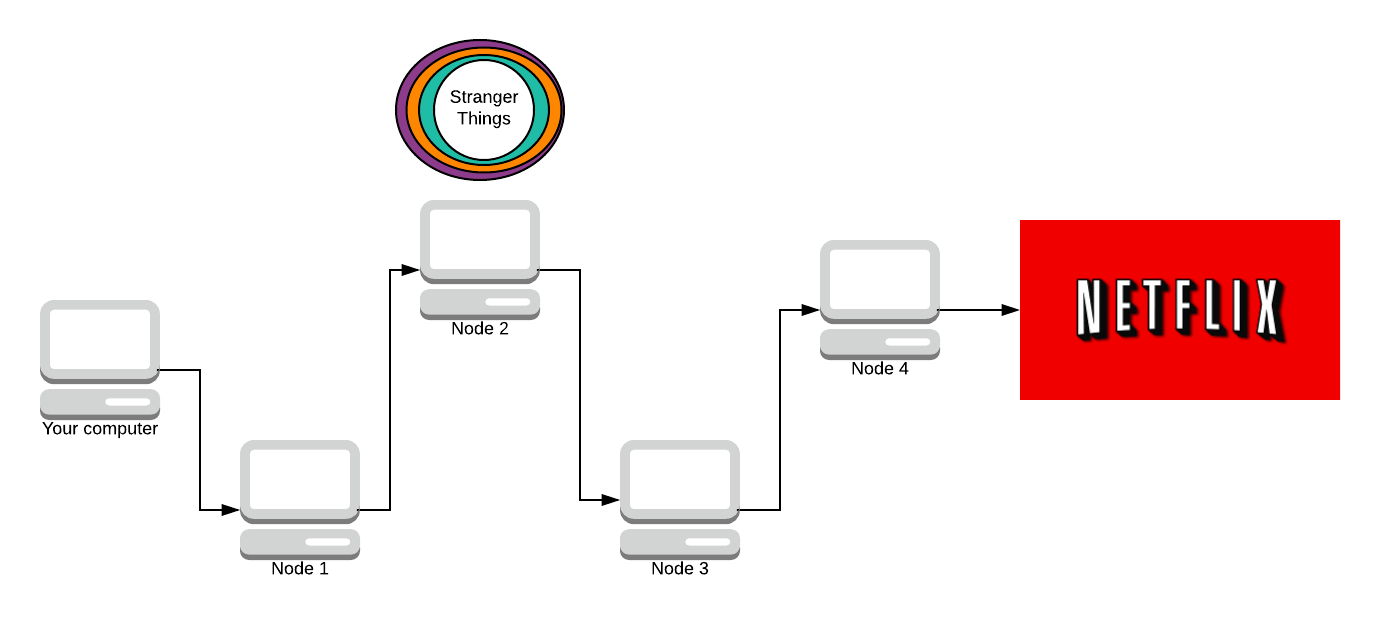

As it travels down the path, more and more layers are stripped away. The next node does not know who sent the packet. All it knows is that Node 1 sent them the packet, and it’s to be delivered to Node 3.

Now Node 3 strips away a layer.

The final node knows what the message is and where it’s going, but it doesn’t know who sent it. All it knows is that Node 3 sent them the message, but it doesn’t know about anyone else in the path. One of the key properties here is that once a node decrypts a layer, it cannot tell how many more layers there are to decrypt. It could be as small as 1 or 2 or as large as 200 layers of encryption.

Now there’s no way Amazon can find out you watch Netflix! Netflix sends back a part of Stranger Things.

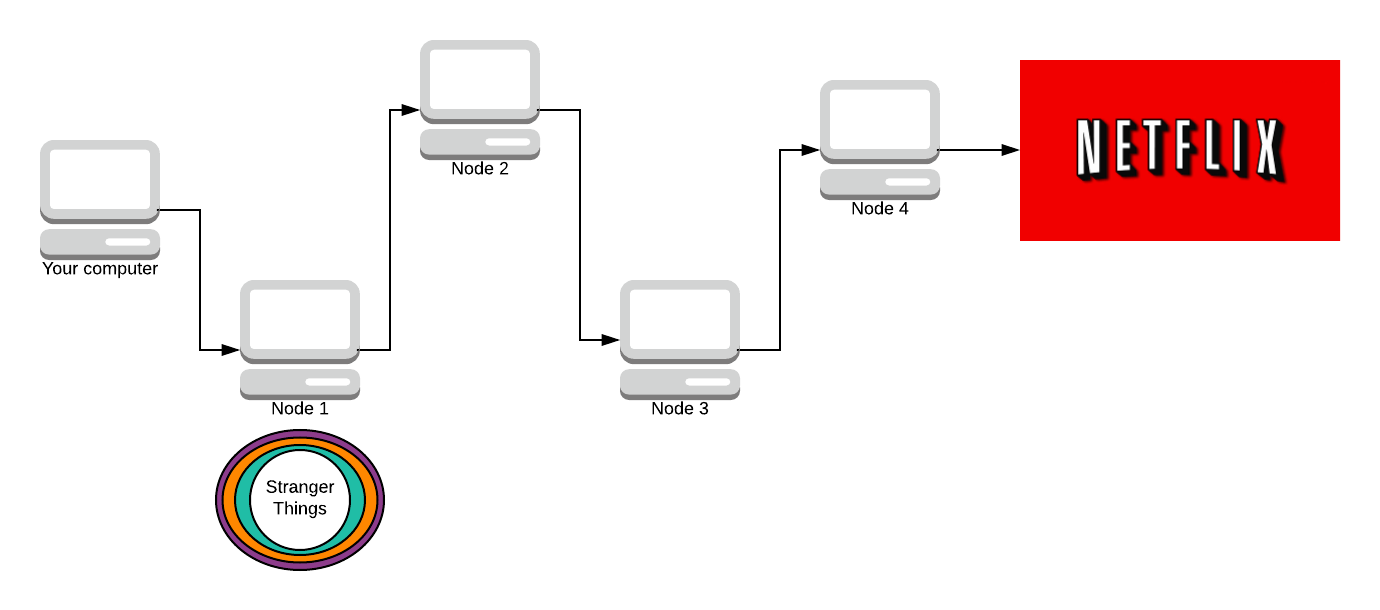

Let’s see how it works in reverse.

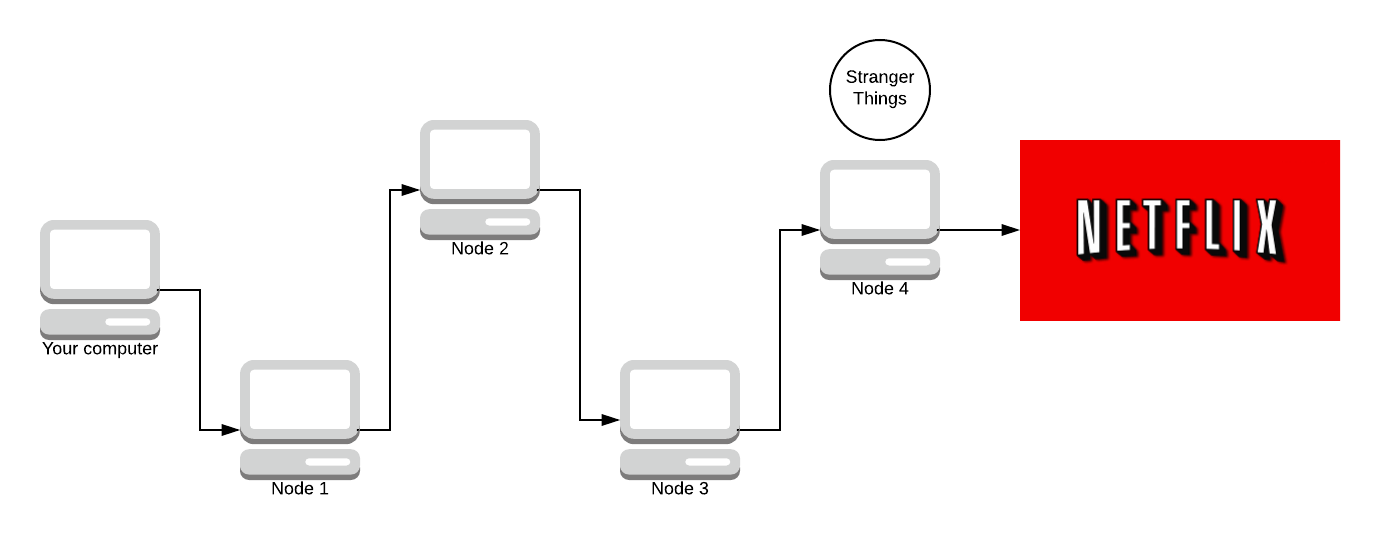

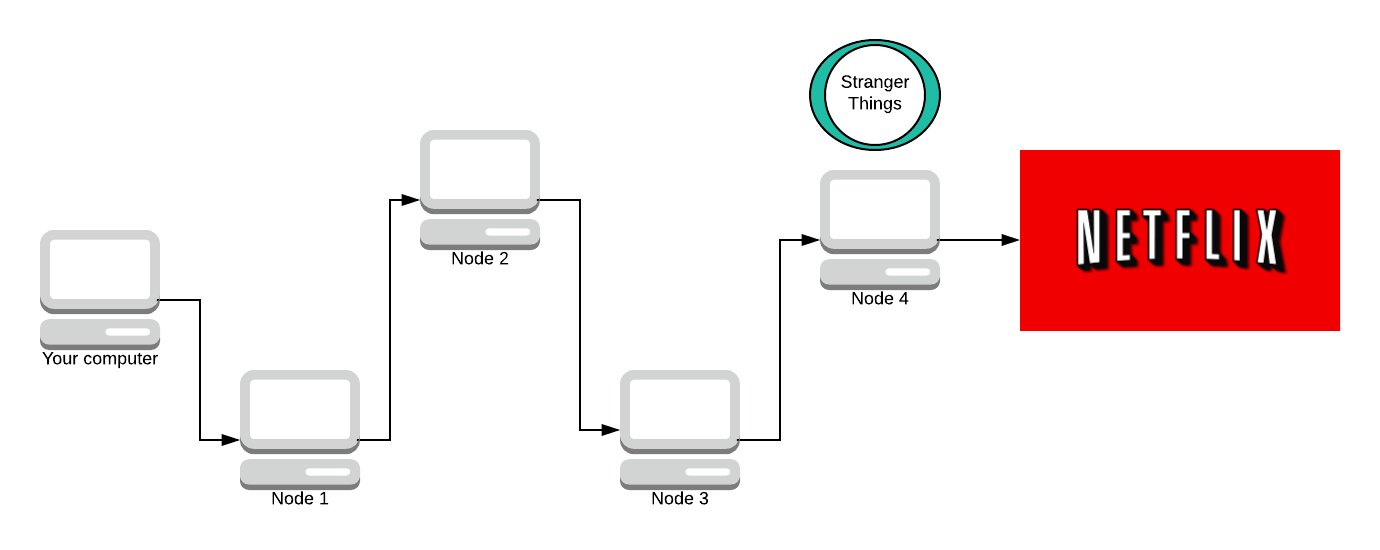

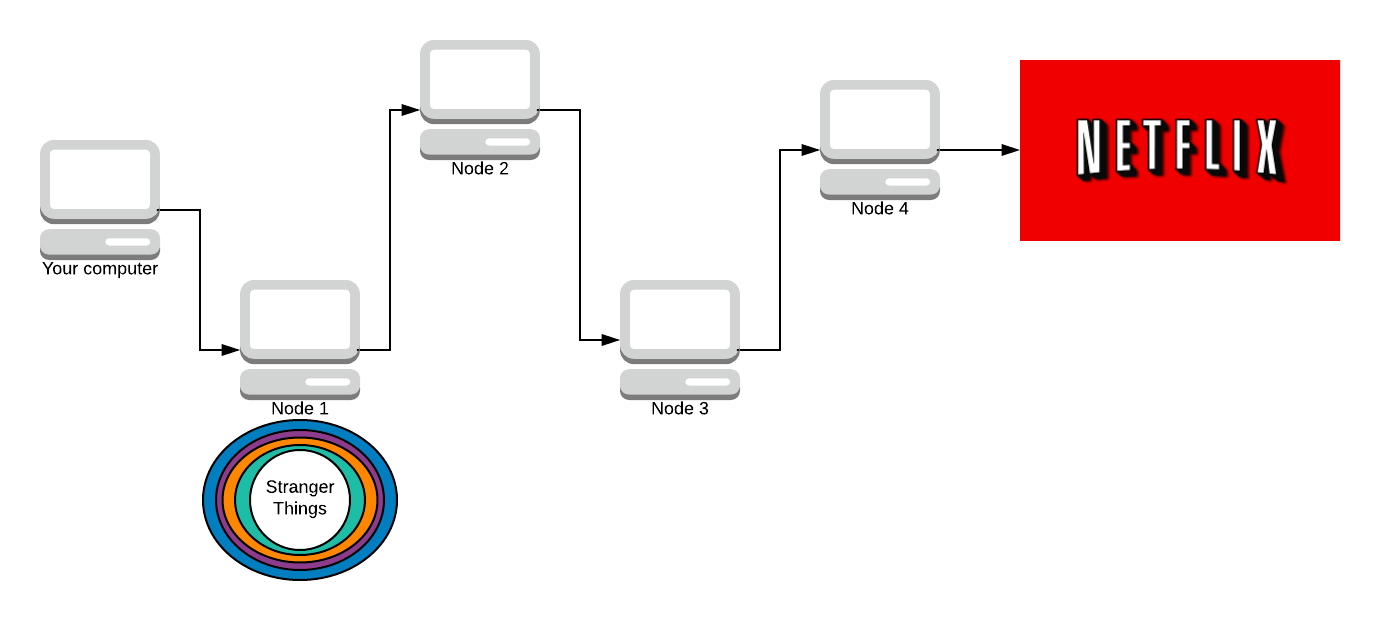

Node 4 adds its layer of encryption now. It doesn’t know who originally made the request, all it knows is that Node 3 sent the request to them so it sends the response message back to Node 3.

And so on for the next few nodes.

Now the response packet is fully encrypted.

Now the packet is fully encrypted, the only one who still knows what the message contains is Node 4. The only one who knows who made the message is Node 1. Now that we have the fully encrypted response back, we can use all the symmetric keys to decrypt it.

You might be thinking “I’ve seen snails 🐌 faster than this” and you would be right. This protocol isn’t designed for speed, but at the same time, it has to care about speed.

The algorithm could be much slower, but much more secure (using entirely public key cryptography instead of symmetric key cryptography) but the usability of the system matters. So yes, it’s slow. No, it’s not as slow as it could be. But it’s all a balancing act here.

The encryption used is normally AES with the key being shared via Diffie-Hellman.

The paths Tor creates are called circuits. Let’s explore how Tor chooses what nodes to use in a circuit.

💻 How Is a Circuit Created?

Each machine, when it wants to create a circuit, chooses the exit node first, followed by the other nodes in the circuit. Tor circuits are always 3 nodes. Increasing the length of the circuit does not create better anonymity. If an attacker owns the first and last nodes in the network, you can have 1500 nodes in the circuit and it still wouldn’t make you more secure.

When Tor selects the exit node, it selects it following these principles:

- Does the client’s

torrc(the configuration file of Tor) have settings about which exit nodes not to choose? - Tor only chooses an exit relay which allows you to exit the Tor network. Some exit nodes only allow web traffic (HTTP/S port 80) which is not useful when someone wants to send an email (SMTP port 25).

- The exit node has to have the available capacity to support you. Tor tries to choose an exit node which has enough resources available.

All paths in the circuit obey these rules:

- We do not choose the same router twice for the same path.

If you choose the same node twice, it’s guaranteed that the node will either be the guard node (the node you enter at) or the exit node, both in dangerous positions. There is a 2/3 chance of it being both the guard and exit nodes, which is even more dangerous. We want to avoid the entry/exit attacks.

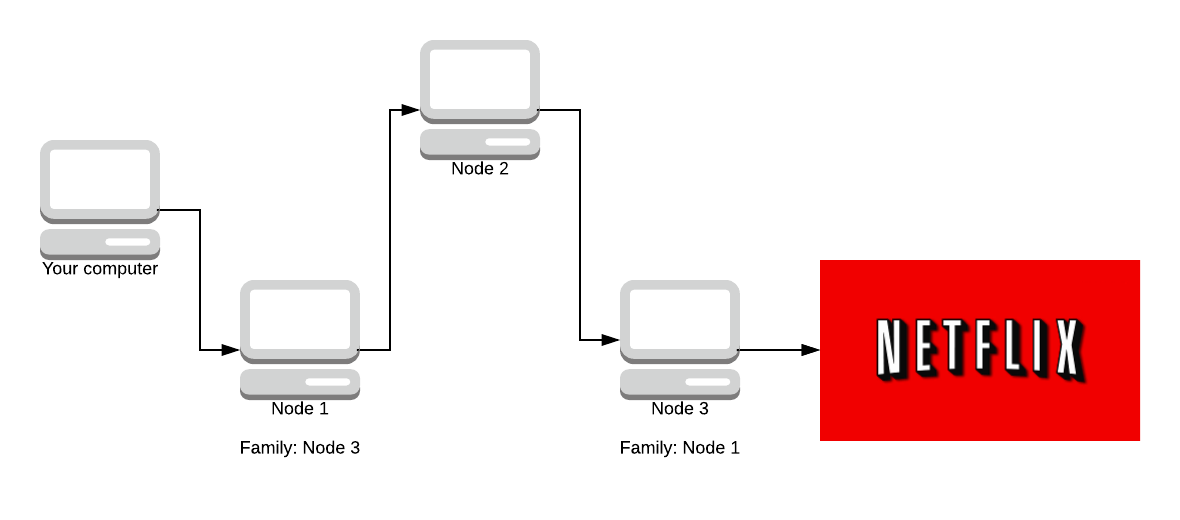

- We do not choose any router in the same family as another in the same path. (Two routers are in the same family if each one lists the other in the “family” entries of its descriptor.)

Operators who run more than 1 Tor node can choose to sign their nodes as ‘family’. This means that the nodes have all the same parent (the operator of their network). This is again a countermeasure against the entry / exit attacks, although operators do not have to declare family if they wish. If they want to become a guard node (discussed soon) it is recommended to declare family, although not required.

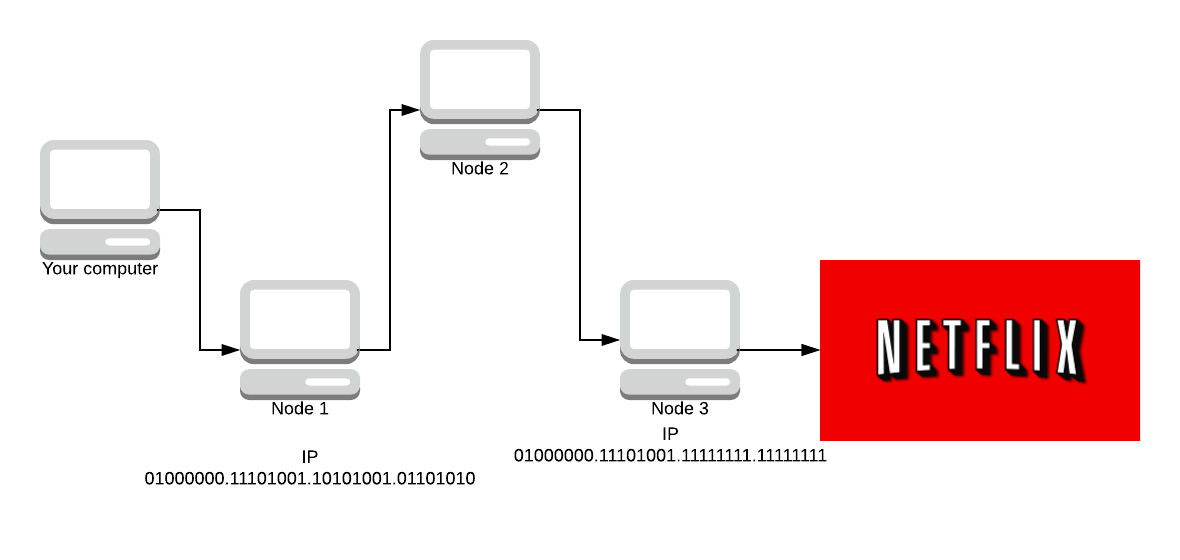

- We do not choose more than one router in a given /16 subnet.

Subnets define networks. IP addresses are made up of 8 octets of bits. As an example, Google’s IP address in binary is:

01000000.11101001.10101001.01101010

The first 16 bits (the /16 subnet) is 01000000.11101001 which means that Tor does not choose any nodes which start with the same 16 bits as this IP address. Again, a counter-measure to the entry/exit attacks.

If subnets sound confusing, I’ve written this Python code to help explain them:

# ip addresses are in binary, not the usual base 10 subnets are usually powers of 2, this is 2^4.

IP = "01000000.11101001.10101001.01101010"

subnet = 16

# this will store the subnet address once we find it

subnet_ip = []

IP_list = list(IP)

counter = 0

for i in IP_list:

# we want to end the loop when we reach the subnet number

if counter >= subnet:

break

# the ip address segments each oclet of bits with full stops

# we don't want to count a fullstop as a number

# but we want to include it in the final subnet

if i == ".":

subnet_ip.append(".")

continue

else:

# else it is a number so we append and increment counter

subnet_ip.append(i)

counter = counter + 1

print("Subnet is " + ''.join(subnet_ip))

- We don’t choose any non-running or non-valid router unless we have been configured to do so. By default, we are configured to allow non-valid routers in “middle” and “rendezvous” positions.

Non-running means the node currently isn’t online. You don’t want to pick things that aren’t online. Non-valid means that some configuration in the nodes torrc is wrong. You don’t want to accept strange configurations in case they are trying to hack or break something.

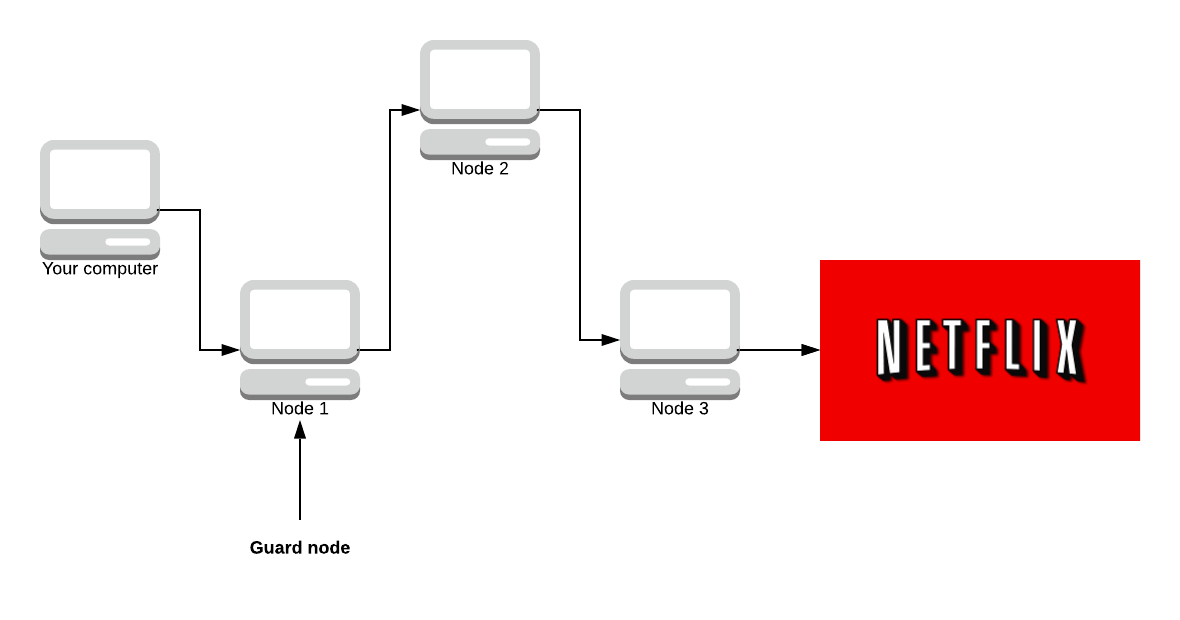

- The first node must be a Guard node.

A guard node is a privileged node because it sees the real IP of the user. It’s ‘expensive’ to become a guard node (maintain a high uptime for weeks and have good bandwidth).

This is possible for large companies that have 99.9% uptime and high bandwidth (such as Netflix). Tor has no way to stop a powerful adversary from registering a load of guard nodes. Right now, Tor is configured to stick with a single guard node for 12 weeks at a time, so you choose 4 new guard nodes a year.

This means that if you use Tor once to watch Amazon Prime Video, it is relatively unlikely for Netflix to be your guard node. Of course, the more guard nodes Netflix creates the more likely it is. Although, if Netflix knows you are connecting to the Tor network to watch Amazon Prime Video then they will have to wait 4 weeks for their suspicions to be confirmed, unless they attack the guard node and take it over.

Becoming a guard node is relatively easy for a large organisation. Becoming the exit node is slightly harder, but still possible. We have to assume that the large organisation has infinite computational power to be able to do this. The solution is to make the attack highly expensive with a low rate of success.

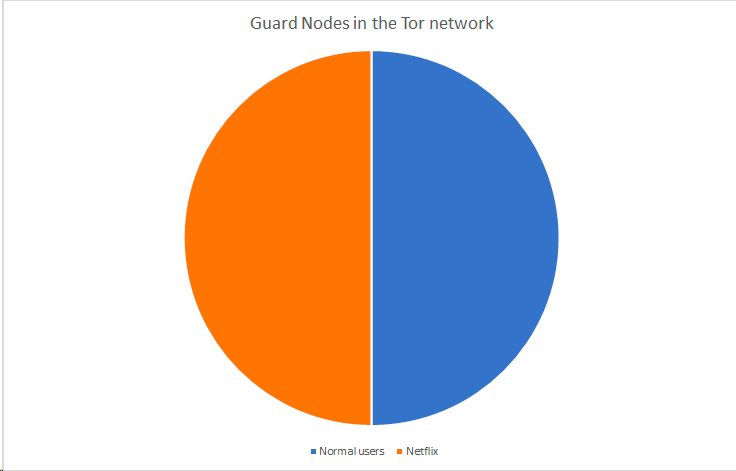

The more regular users of Tor, the harder is if for a large organisation to attack it. If Netflix controls \(\frac{50}{100}\) nodes in the network:

The chance of you choosing a guard node from Netflix is 50%.

If suddenly 50 more normal user nodes join then that’s $\frac{50}{150}$, reducing the probability of Netflix owning a guard node (and thus, a potential attack) and making it even more expensive.

There is strength in numbers within the Tor service.

📌 Guard Pinning

When a Tor client starts up for the first time, it chooses a small & random set of guard nodes. For the next few months, it makes sure each circuit is using one of these pre-selected nodes as its guard node.

The official proposal from the Tor documentation states:

1. Introduction and motivation

Tor uses entry guards to prevent an attacker who controls some

a fraction of the network from observing a fraction of every user's

traffic. If users chose their entries and exits uniformly at

random from the list of servers every time they build a circuit,

then an adversary who had (k/N) of the network would deanonymize

F=(k/N)^2 of all circuits... and after a given user had built C

circuits, the attacker would see them at least once with

probability 1-(1-F)^C. With large C, the attacker would get a

sample of every user's traffic with probability 1.

To prevent this from happening, Tor clients choose a small number

of guard nodes (currently 3). These guard nodes are the only

nodes that the client will connect to directly. If they are not

compromised, the user's paths are not compromised.

But attacks remain. Consider an attacker who can run a firewall

between a target user and the Tor network, and make many of the

guards they don't control appear to be unreachable. Or consider

an attacker who can identify a user's guards, and mount

denial-of-service attacks on them until the user picks a guard

that the attacker controls.

Guard node pinning is important because of Tor’s threat model. Tor assumes that it may only take a single opening for an adversary to work out who you are talking to, or who you are. Since a single vulnerability circuit can destroy your integrity, Tor tries to minimise the probability that we will ever construct one or more vulnerable circuits.

Tor guard nodes can be DOS’d, or an attacker could have a majority share of guard nodes on the internet when you connect to try and get you. By guard node pinning, it aims to make this much harder.

In the event of an attacker working out your guard nodes and shutting them down, forcing you to connect to their guard nodes. Or, you connect to a guard node controlled by an adversary Tor has algorithms in place to try and detect this. Outined here.

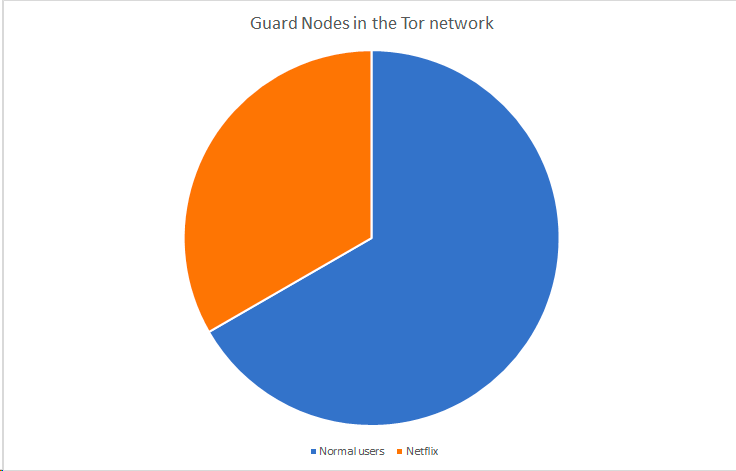

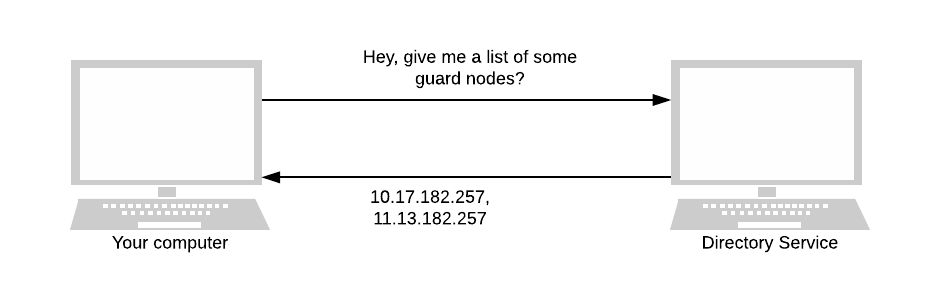

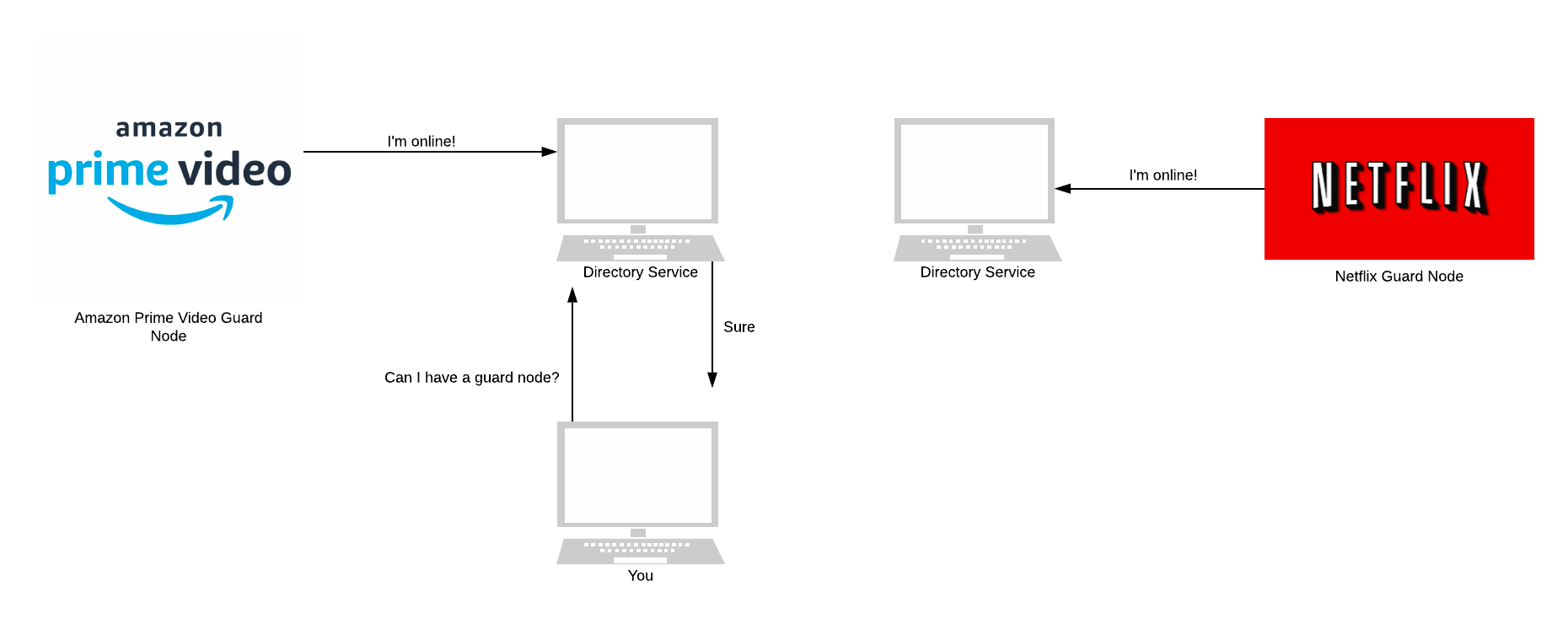

📂 What Is a Directory Node?

The state of the Tor network is tracked and publicised by a group of 9 trusted servers (as of 2019) known as directory nodes. Each of these is controlled by a different organisation.

Each node is a separate organisation because it provides redundancy and distributes trust. The integrity of the Tor network relies on the honesty and correctness of the directory nodes. So making the network resilient and distributing trust is critical.

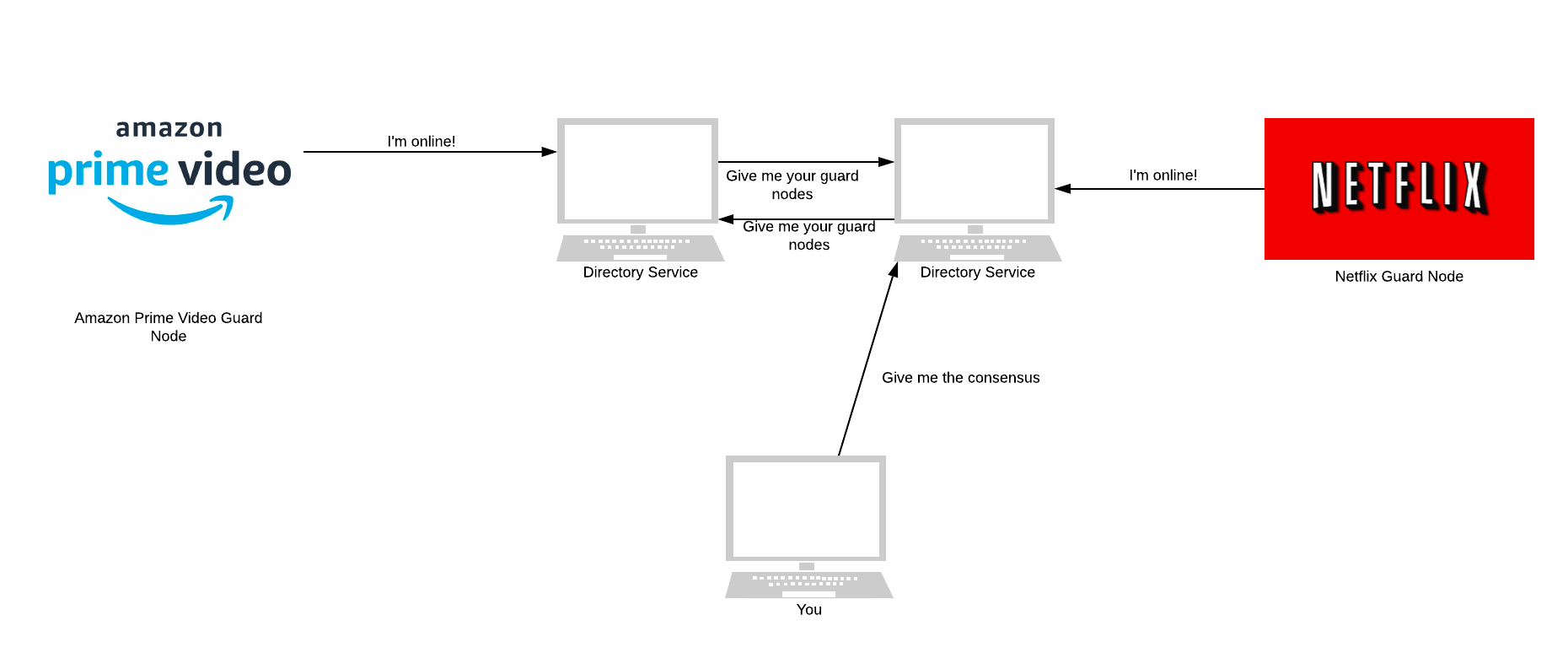

Directory nodes maintain a list of currently running relays (publicly listed node in the Tor network). Once per hour, directory nodes publish a consensus together. The consensus is a single document compiled and voted on by each directory node. It ensures that all clients have the same information about the relays that make up Tor.

When a Tor user (a client or a node) wants to know the current state of the network, it asks for a directory node. As we’ll see later, directory nodes are essential for all parts of Tor, especially in hidden services.

Relays keep the directory nodes up to date. They send directory node(s) a notification whenever they come online or are updated. Whenever a directory node receives a notification, it updates its personal opinion on the current state of the Tor network. All directory nodes then use this opinion to form a consensus of the network.

Let’s now look at what happens when disagreements arise in the directory services when forming a consensus.

The first version of Tor took a simple approach to conflict resolution. Each directory node gave the state of the network as it personally saw it. Each client believed whichever directory node it had spoken to recently. There is no consensus here among all directory nodes.

In Tor, this is a disaster. There was nothing ensuring that directory nodes were telling the truth. If an adversary took over one directory node, they would be able to lie about the state of the network.

If a client asked this adversary-controlled directory for the state of the network, it’d return a list. This list contains only nodes that the adversary controlled. The client would then connect to these adversary nodes.

The second version of the Tor directory system made this attack harder. Instead of asking a single directory node for its opinion, clients asked every directory node and combined their opinions into a consensus. But, clients could form differing views on the network depending on when they had last spoken to each directory node. This gave way to statistical information leakage - not as bad as Tor 1.0. Besides, every client had to talk to every directory node, which took time and was expensive.

The third and current version of the directory system moved the responsibility of calculating a consensus from clients to directory nodes.

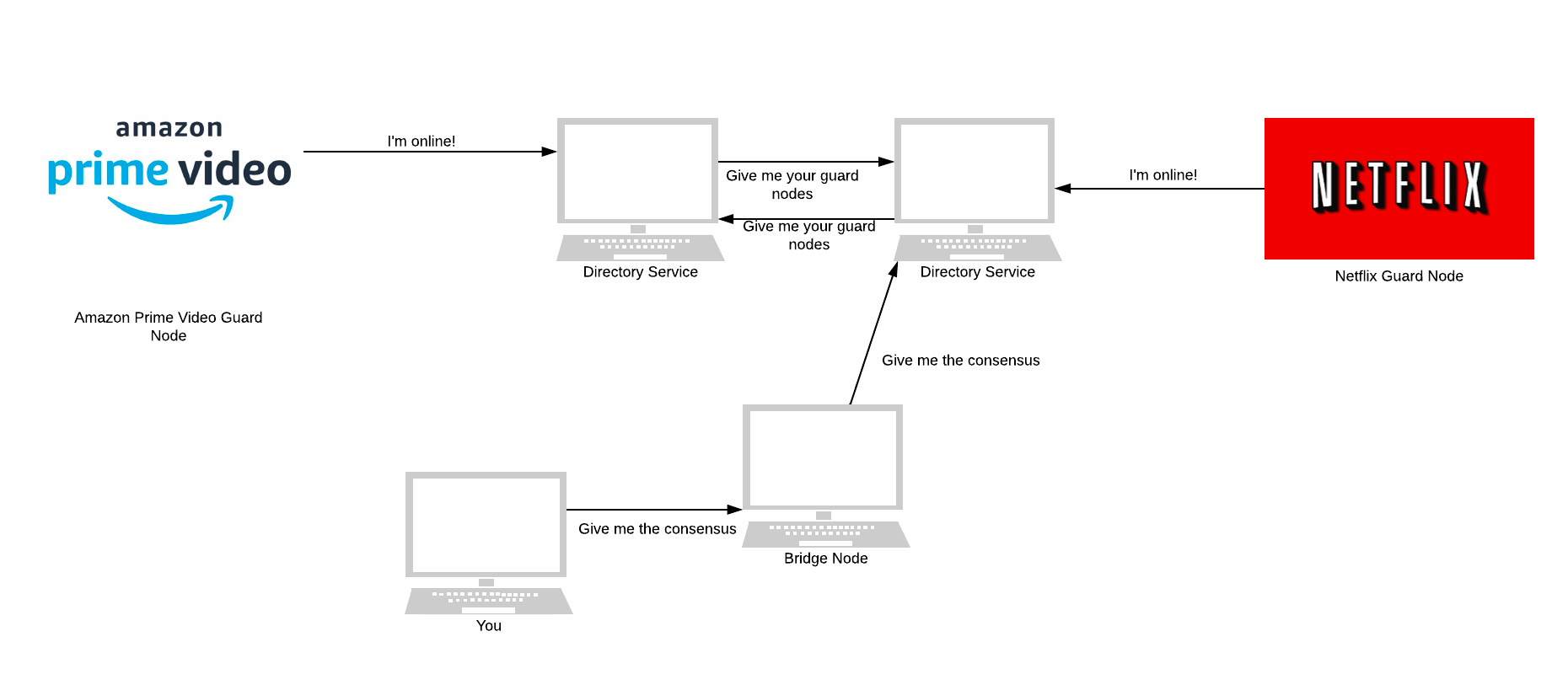

🌉 What Are Bridge Nodes?

I’m not sure if you saw it earlier, but I made the distinction between nodes in the directory services and nodes that aren’t.

If a repressive state wants to block Tor, it uses the directory nodes. Directory nodes keep up-to-date lists of Tor relay nodes and are publicly available for anyone to download.

The state can query a directory node for a list of active Tor relays, and censor all traffic to them.

Tor keeps an up-to-date listing of countries where it is possibly blocked (censored) if you’re interested.

Tor helps its users circumvent censorship by hiding the fact they are using Tor. They do this through a proxy known as a Bridge Node. Tor users send their traffic to the bridge node, which forwards the traffic to the user’s chosen guard nodes.

The full list of Bridge nodes is never published, making it difficult for states to completely block Tor. You can view some bridge nodes here. If this doesn’t work, Tor suggests:

Another way to get bridges is to send an email to bridges@torproject.org. Please note that you must send the email using an address from one of the following email providers: Riseup or Gmail.

It’s possible to block Tor another way. Censoring states can use Deep Packet Inspection (DPI)to analyse the shape, volume, and feel of each packet. Using DPI states can recognise Tor traffic, even when they connect to unknown IP addresses or are encrypted.

To circumvent this, Tor developers have made Pluggable Transports (PT). These transform Tor traffic flow between the client and the bridge. In the words of Tor’s documentation:

This way, censors who monitor traffic between the client and the bridge will see innocent-looking transformed traffic instead of the actual Tor traffic. External programs can talk to Tor clients and Tor bridges using the pluggable transport API, to make it easier to build interoperable programs.

🕵️♀️ Tor Hidden Services

Ever heard those rumours “There are websites on the dark web, on Tor that when you visit them you’ll see people doing nasty things, selling illegal things or worse: watching The Hangover Part 3”

When people talk about these websites they are talking about Tor Hidden Services.

These are a wild concept and honestly deserve an entire blog post on their own. Hidden services are servers, like any normal computer server.

Except in a Tor Hidden Service, it is possible to communicate without the user and server knowing who each other is.

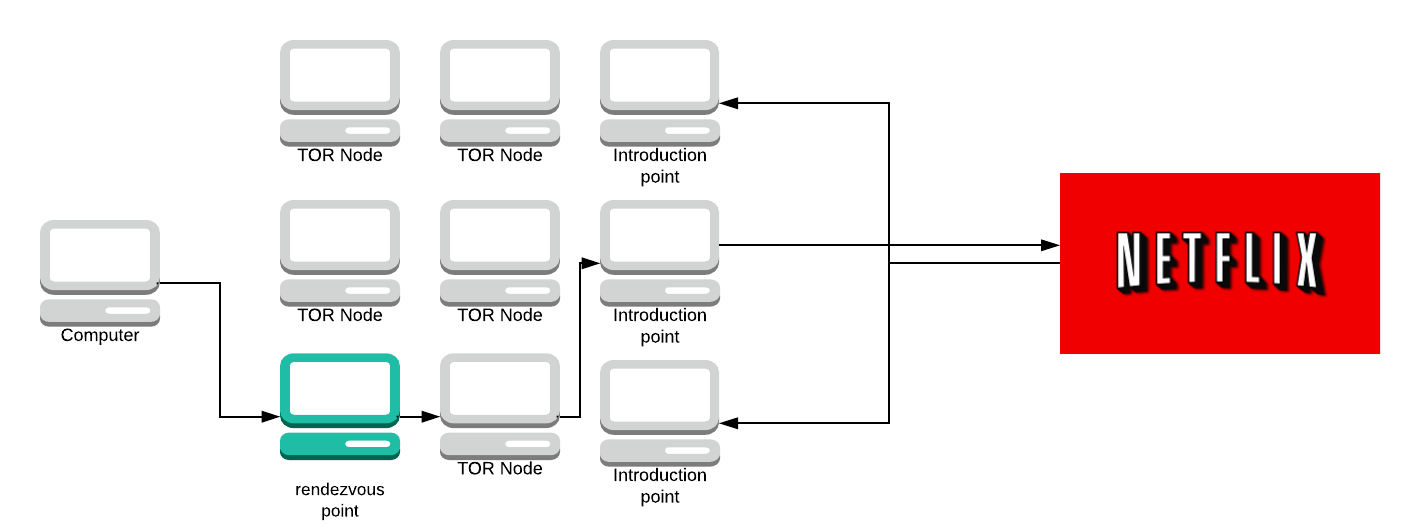

The device (the question mark) knows that it wants to access Netflix, but it doesn’t know anything about the server and the server doesn’t know anything about the device that’s asked to access it. This is quite confusing, but don’t worry, I’m going to explain it all with cool diagrams. ✨

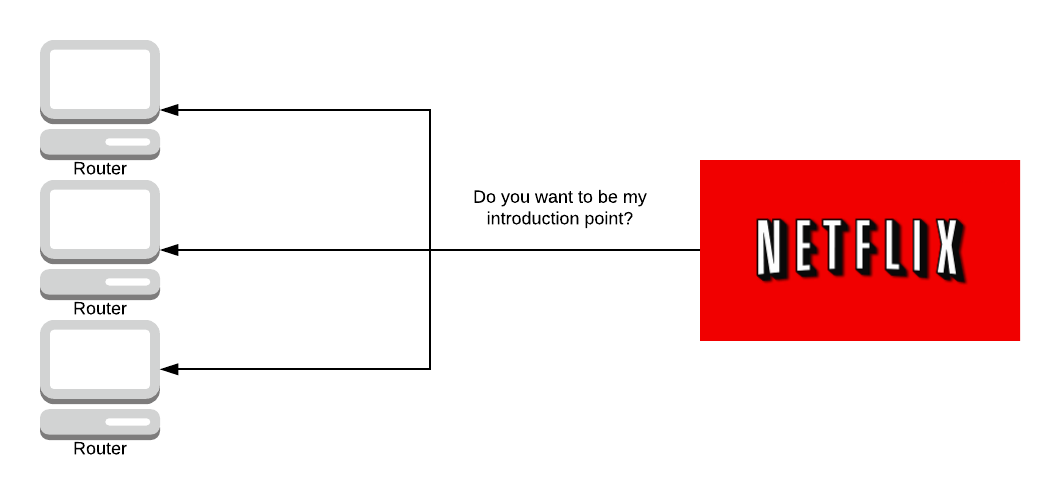

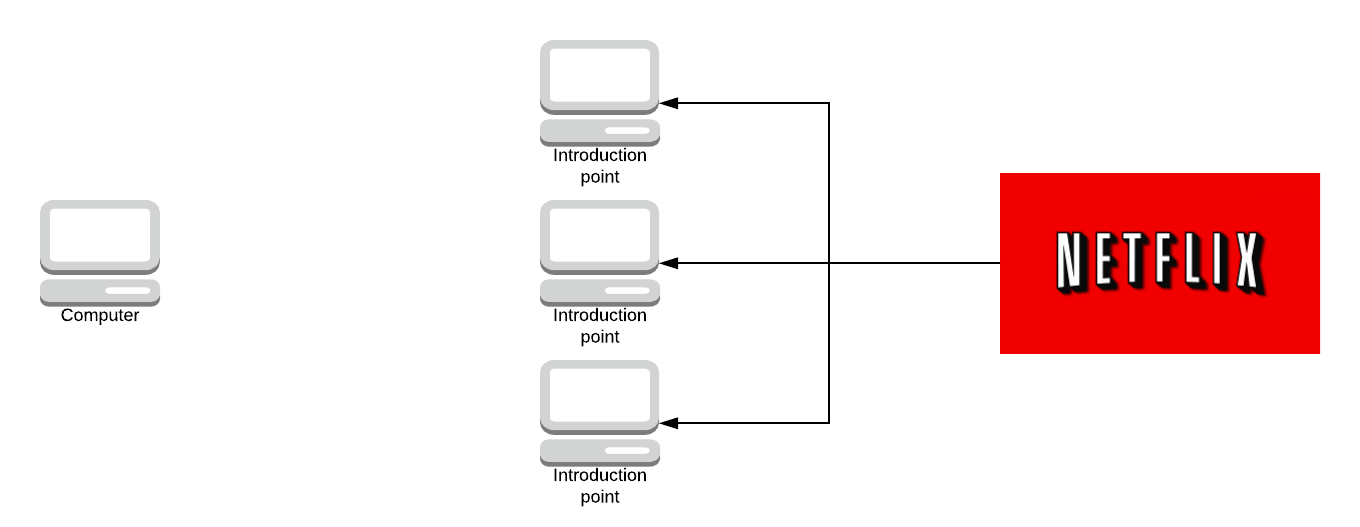

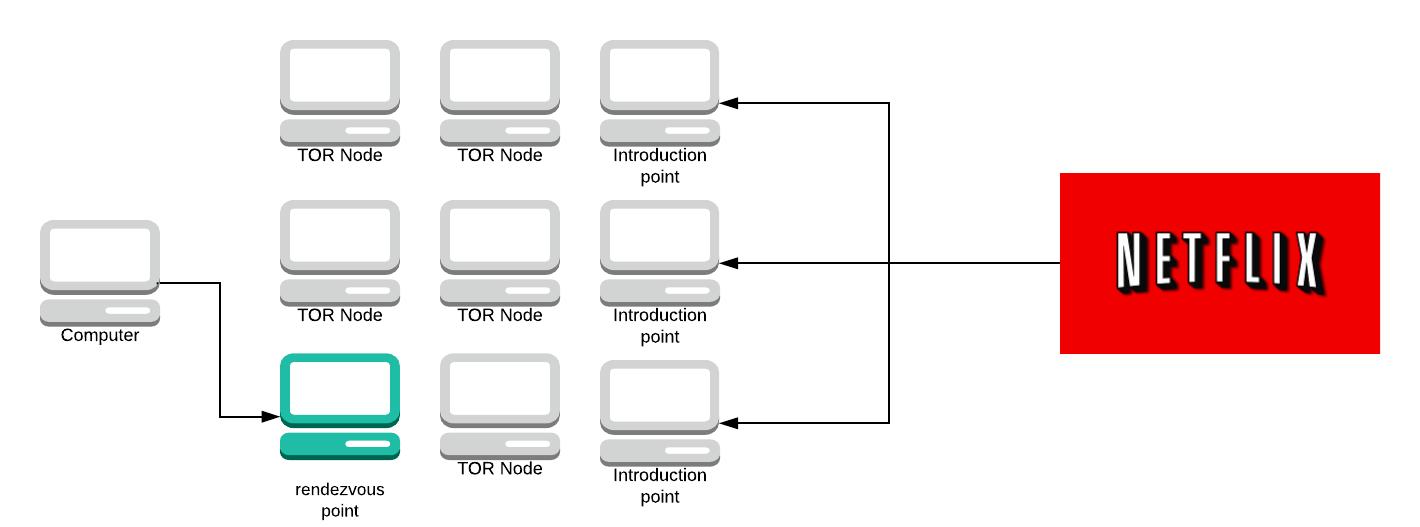

When a server is set up on Tor to act as a hidden service, the server sends a message to some selected Onion Routers asking if they want to be an introduction point to the server. It is entirely up to the server as to who gets chosen as an introduction point, although usually, they ask 3 routers to be their introduction points.

The introduction points know that they are going to be introducing people to the server.

The server will then create something called a hidden service descriptor which has a public key and the IP address of each introduction point. It will then send this hidden service descriptor to a distributed hash table which means that every onion router (not just the introduction points) will hold some part of the information of the hidden service.

If you try to look up a hidden service the introduction point responsible for it will give you the full hidden service descriptor, the address of the hidden service’s introduction points.

The key for this hash table is the onion address and the onion address is derived from the public key of the server.

The idea is that the onion address isn’t publicised over the whole Tor network but instead, you find it another way like from a friend telling you or on the internet (addresses ending in .onion).

The way that the distributed hash table is programmed means that the vast majority of the nodes won’t know what the descriptor is for a given key.

So almost every single onion router will have minimal knowledge about the hidden service unless they explicitly want to find it.

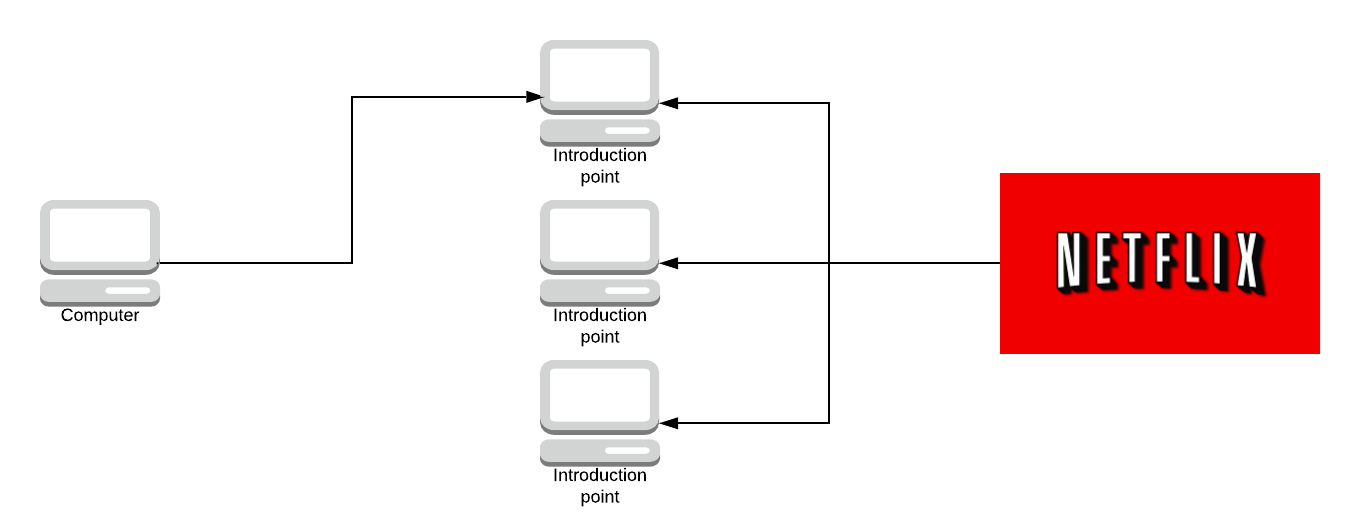

Let’s say someone gave you the Onion address. You request the descriptor off the hash table and you get back the services introduction points.

If you want to access an onion address you would first request the descriptor from the hash table and the descriptor has, let’s say 4 or 5 IP addresses of introductory nodes. You pick one at random let’s say the top one.

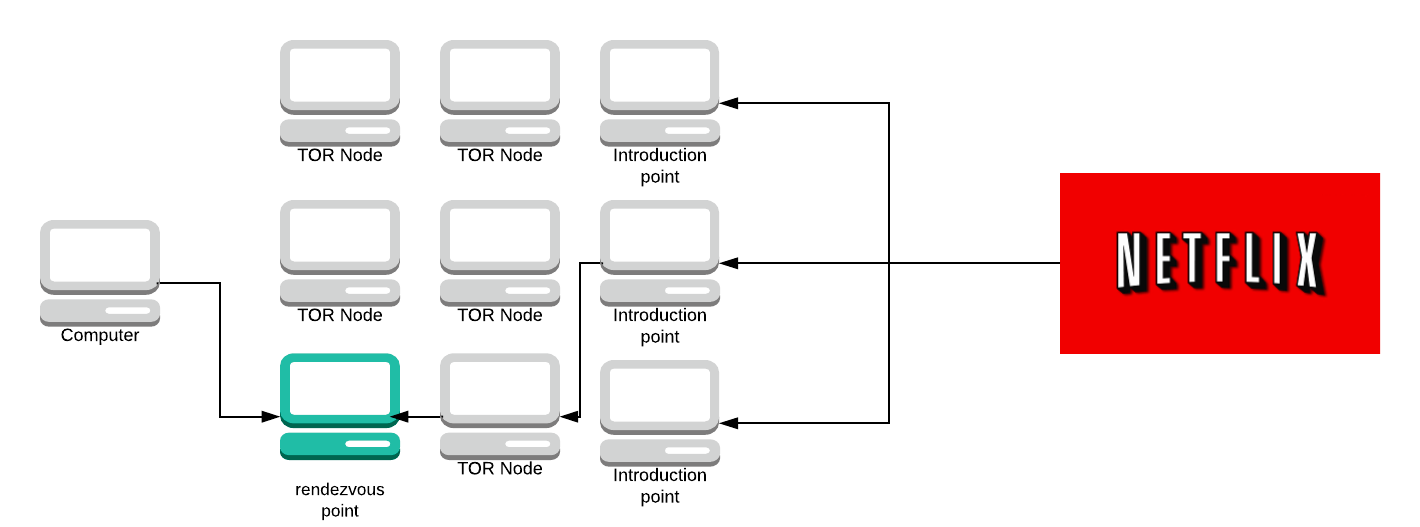

You’re going to ask the introduction point to introduce you to the server and instead of making a connection directly to the server, you make a rendezvous point at random in the network from a given set of Onion Routers.

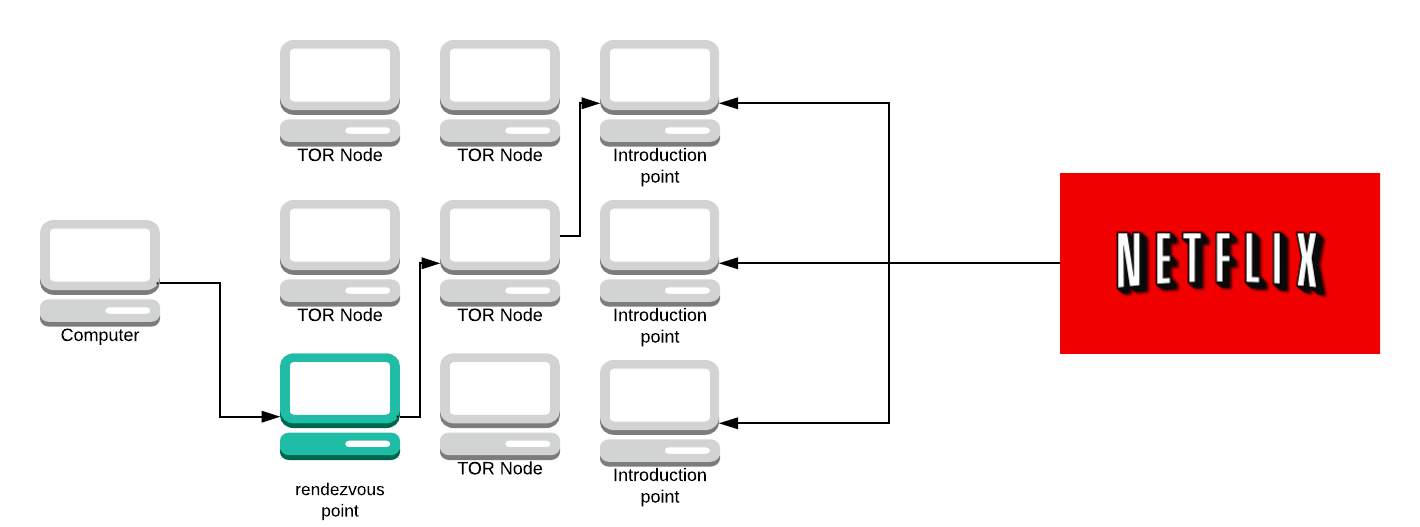

This should say “Tor node”. I’ve lost the files for these graphs (thanks LucidChart). Terribly sorry I can’t update this. You then make a circuit to that rendezvous point and you send a message to the rendezvous point asking if it can introduce you to the server using the introduction point you just used. You then send the rendezvous point a one-time password (in this example, let’s use ‘Labrador’).

The rendezvous point makes a circuit to the introduction point and sends it the word ‘Labrador’ and its IP address.

The introduction point sends the message to the server and the server can choose to accept it or do nothing.

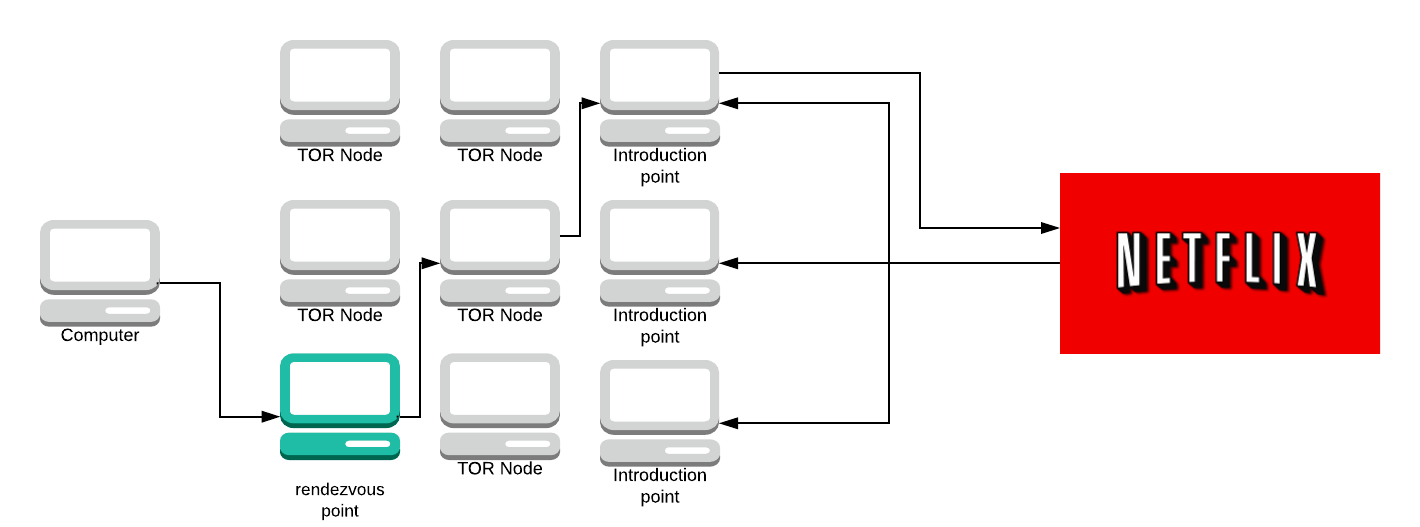

If the server accepts the message it will then create a circuit to the rendezvous point.

The server sends the rendezvous point a message. The rendezvous point looks at both messages from your computer and the server. It says “well, I’ve received a message from this computer saying it wants to connect with this service and I’ve also received a message from the service asking if it can connect to a computer, therefore they must want to talk to each other”.

The rendezvous point will then act as another hop on the circuit and connect them.

In short, a hidden service works like this, taken from here:

- A hidden service calculates its key pair (private and public key, asymmetric encryption).

- Then the hidden service picks some relays as its introduction points.

- It tells its public key to those introduction points over Tor circuits.

- After that, the hidden service creates a hidden service descriptor, containing its public key and what its introduction points are.

- The hidden service signs the hidden service descriptor with its private key.

- It then uploads the hidden service descriptor to a distributed hash table (DHT).

- Clients learn the .onion address from a hidden service out-of-band. (e.g. public website) (A $hash.onion is a 16-character name derived from the service’s public key.)

- After retrieving the .onion address the client connects to the DHT and asks for that $hash.

- If it exists the client learns about the hidden service’s public key and its introduction points.

- The client picks a relay at random to build a circuit to it, to tell it a one-time secret. The picked relay acts as a rendezvous point.

- The client creates a introduce message, containing the address of the rendezvous point and the one-time secret, before encrypting the message with the hidden service’s public key.

- The client sends its message over a Tor circuit to one of the introduction points, demanding it to be forwarded to the hidden service.

- The hidden service decrypts the introduced message with its private key to learn about the rendezvous point and the one-time secret.

- The hidden service creates a rendezvous message, containing the one-time secret and sends it over a circuit to the rendezvous point.

- The rendezvous point tells the client that a connection was established.

- Client and hidden service talk to each other over this rendezvous point. All traffic is end-to-end encrypted and the rendezvous point just relays it back and forth. Note that each of them, client and hidden service, builds a circuit to the rendezvous point; at three hops per circuit, this makes six hops in total.

🤺 Attacks on Tor

Tor protects its users from analysis attacks. The adversary wants to know who Alice is talking to. Yet, Tor does not protect against confirmation attacks. In these attacks, the adversary aims to answer the question “Is Alice talking to Bob?”

Confirmation attacks are hard and need a lot of preparation and resources. The attacker needs to be able to track both ends of the circuit. The attacker can either directly track each device's internet connection or the guard and exit nodes.

If Alice sends a packet like this:

# (timestamp, size, port, protocol)

(17284812, 3, 21, SSH)

When Bob receives this packet, the attacker can see that the packets are the same - even though the attacker cannot see what the packet is as it is encrypted. Does Bob tend to receive packets at the same time that Alice sends them? Are they the same size? If so, it is reasonable to infer that Alice and Bob are communicating with each other.

Tor breaks packets up into sizeable chunks for a reason - to try and prevent this kind of thing. Tor is working on padding all packets to make this harder.

They’re discussing adding packet order randomisation too. But this is too costly at the moment. The Tor browser does add some extra defences, such as reordering packets.

If Alice sends the packets, A, B, C and Bob receives them in B, A, C it is harder to detect that they are the same. It’s not foolproof, but it does become harder.

An attack where the attacker tries to control both ends of the circuit is called a Sylbil Attack. Named after the main character of the book Sybil by Flora Rheta Schreiber. We discussed some of this earlier, where an attacker controls both the guard & exit nodes.

Sybil attacks are not theoretical. In 2014 researchers at Carnegie Mellon University appeared to successfully carry out a Sybil Attack against the real-life Tor network.

When Lizard Squad - a group of hackers tried to perform a Sybil attack, a detection system alarmed. Tor has built-in monitoring against these kinds of events, and they are working on more sophisticated monitoring against Sybil attacks.

In 2007 Dan Egerstad - a Swedish security consultant, revealed he has intercepted usernames and passwords sent through Tor by being an exit node. At the time, these were not TLS or SSL encrypted.

Interestingly, Dan Egerstad had this to say on the Tor nodes:

If you actually look into where these Tor nodes are hosted and how big they are, some of these nodes cost thousands of dollars each month just to host because they’re using lots of bandwidth, they’re heavy-duty servers and so on. Who would pay for this and be anonymous?

Tor does not normally hide the fact that you are using Tor. Many websites (such as BBC’S iPlayer or editing Wikipedia) block you when using a known Tor node.

Some applications, under Tor, reveal your true IP address. One such application is BitTorrent.

Jansen et al described an attack where they DDOS exit nodes. By degrading the network (removing exit nodes) an attacker increases the chance to getting an exit node.

Tor users who visit a site twice, once on Tor and once off, can be tracked. The way you move your mouse is unique. There is a JavaScript time measurement bug report on the Tor project that shows how it’s possible to monitor the mouse locations on a site (even when on Tor). Once you fingerprint someone twice, you know they’re the same person.

It should be noted, that Tor browser offers 3 levels of security (located in the settings). The highest security level disables JavaScript, some images (as they can be used to track you) and some fonts too. The lesson is, if you want high-security Tor, use the high-security version.

Now, all these attacks sound cool. But that’s not how most Tor users are caught. Most Tor users make mistakes and are caught because of themselves.

Take Dredd pirate Roberts, Founder of the Silk Road dark marketplace. He gave himself away by posting about it on social media.

Most Tor users are caught (if they’re doing illegal things) by bad operational security, and not normally because of a security issue with Tor.

It’s worth repeating this story, that we saw earlier.

In 2013 during the Final Exams period at Harvard, a student tried to delay the exam by sending in a fake bomb threat. The student used Tor and Guerrilla Mail (a service which allows people to make disposable email addresses) to send the bomb threat to school officials.

The student was caught, even though he took precautions to make sure he wasn’t caught.

Guerilla mail sends an originating IP address header along with the email that’s sent to the receiver, so it knows where the original email came from. With Tor, the student expected the IP address to be scrambled but the authorities knew it came from a Tor exit node (Tor keeps a list of all nodes in the directory service) so the authorities looked for people who were accessing Tor (within the university) at the time the email was sent.

If this person went to a coffee shop or something, he probably would be fine.

There’s a fantastic talk at DEFCON 22 about how Tor users got caught. None of the stories mentioned was caused by Tor, but rather bad OpSec.

📕 Conclusion

Tor is a fascinating protocol full of algorithms that have been refined over the years. I’ve come to appreciate Tor, and I hope you have to. Here is a list of things we’ve covered:

- What Tor is

- What Tor Isn’t

- Attacks on the Tor network

- Onion Routing

- How circuits are made

- How nodes in a circuit are selected

- How hidden services work

If you want to learn more, check out the paper on Tor titled “Tor: The Second-Generation Onion Router".

If you liked this article and want more like it, sign up to my email list below ✨ I’ll only send you an email when I have something new, which is every month / 2 month or so.